The 1980s were a

battle between what eventually became New Labour, and what is often

referred to as the Hard Left. 1983 to 1997 was a long period where

the Hard Left gradually lost influence within both the party (then

the membership and trade unions) and among the parliamentary party

(the PLP). But this didn’t mollify the distaste New Labour had for

the Hard Left.

This period meant

that those opposing the left adopted two propositions which became

almost hard-wired into their decisions.

-

The left

within Labour were more concerned with controlling the party than

winning elections. That has often been said about Jeremy Corbyn over the last two years.

-

That the Left, and their ideas and policies, were toxic to most voters. The

right wing press assisted in this by talking about the loony left.

In short, it was

best to act as if Labour’s Left were a political pariah. As a

result of these ideas the left minority within the PLP was tolerated

(Labour needed to be a broad church), as long as it remained small

and powerless. Triangulation became the way to win power: to adopt

policies that were never from the Left, but adopted a centre ground

between the Left and the Conservatives. New Labour was not old

Labour.

The strategy was

extremely successful. Tony Blair won three elections, and it took the

deepest recession since the 1930s to (just) remove Labour from

office. The Blair government achieved a lot, particularly for the

poor, but it also made serious mistakes, most notably Iraq. That

stopped a lot of those on the left actively supporting the party.

In 2015, when Labour

under Ed Miliband was defeated, the general mood among the PLP seemed

to be that it needed to triangulate once more and move further to the

right. Crucially, some leading figures suggested Labour should all

but embrace George Osborne’s austerity policy. The three main

candidates to take over from Miliband were seen (with justification

or not) as representing this thinking. Austerity was a critical

issue, in part because - if accepted - it potentially constrained

what Labour could do to a large extent. It was also an economically

illiterate policy, which I can safely say with authority. Worse than

that, it was a policy that - as the deficit fell - began to lose its popularity, so for Labour to adopt it at just the point it was

losing its popular appeal seemed a doubly crazy thing to do.

Before Corbyn won

that election I wrote

“Whether Corbyn wins or loses, Labour MPs and associated politicos

have to recognise that his popularity is not the result of entryism,

or some strange flight of fancy by Labour’s quarter of a million

plus members, but a consequence of the political strategy and style

that lost the 2015 election. …. A large proportion of the

membership believe that Labour will not win again by accepting the

current political narrative on austerity or immigration or welfare or

inequality and offering only marginal changes to current government

policy.”

At this point I was receiving impassioned pleas by some to come out

against Corbyn. These mainly went along the lines that Corbyn was

unreformed from the 70s/80s, and wanted to take over the party for

the ‘old left’. Many said he could not win an election because

his policies would be too radical. He would be a disaster with the

electorate. It was unmodified 1980s thinking. These arguments sounded

unconvincing to me, mainly because Corbyn would have to work with the PLP.

Unlike the 1980s, the left were now such a small minority within the

PLP that they would have no other choice.

As I had

anticipated, Corbyn and McDonnell did form a shadow cabinet of all the

(willing) talents, and as far as economic policy was concerned they

were far from radical. McDonnell set up the Economic Advisory Council

(EAC), which I and I suspect others were happy to join because it

involved no endorsement of Labour’s policies. Arguments that we

should have withheld our advice because Corbyn was somehow ‘beyond

the pale’ were again straight from the post-83 playbook, and I am

very glad that I ignored them. I helped Labour adopt a fiscal rule

which in my view exemplified where mainstream macroeconomics was, and

which incidentally some sections of the Left were very critical of.

It formed a key part of their 2017 manifesto

What I had not

anticipated, back when Corbyn was about to be elected, was how

foolish some Labour MPs would be in those months following his

election. Critical briefing of the press was constant, and tolerated

by many in the PLP. As I wrote at the time, this strategy was stupid

even if you hated Corbyn, because it gave the membership the excuse

to ignore Corbyn’s failings. I was more right than I could have

imagined. This was the first major mistake that the PLP made after

the election.

The other thing I

had not anticipated was Brexit. This triggered the second major

mistake by the PLP, which was the vote of no confidence. It was in

many cases

an emotional reaction to Brexit, the leadership’s role in the

campaign and earlier incompetence. It was understandable, but it was

nevertheless terrible politics. Corbyn’s supporters were gifted the

perfect narrative in the subsequent leadership election: the PLP had

sabotaged Corbyn’s leadership.

The two mistakes

made by the PLP ensured that for many members the 2016 vote became

the PLP against the membership. One big mistake Owen Smith made was

to not side with the membership in terms of changing the 15%

leadership rule, so naturally they said if you do not trust us we

will not trust you. Nevertheless I supported Smith over Corbyn,

because I could not see a future for a party that had become so deeply divided. I thought the next election was winnable for Labour, but not

if the party was seen by the electorate as at war with itself. That was one of

the key reasons I resigned from the EAC: whether that was the reason

three others also left I cannot say.

After Corbyn won for

a second time, the polls suggested Labour’s future was bleak. This

is what led May to call her snap election. However two things

happened after Corbyn’s re-election which surprised me and many others, and meant that my predictions of no future under Corbyn proved wrong.

First, the internal squabbling within Labour stopped almost

completely. Second, the leadership started putting together a

manifesto that would prove very popular, with a competence that had

earlier been missing. During the general election divisions within Labour

were not part of May’s main attack, in part because she chose to

make the campaign presidential in style..

Many will say that Labour achieving 40% of the popular vote vindicated the

membership’s faith in Corbyn. Others will go further and say ‘if

only the PLP had been more cooperative we could have won’. That is

going too far..The election result was also a consequence of a truly

terrible Conservatives campaign, headed by a Prime Minister who

exposed herself as just the wrong person to lead the country through

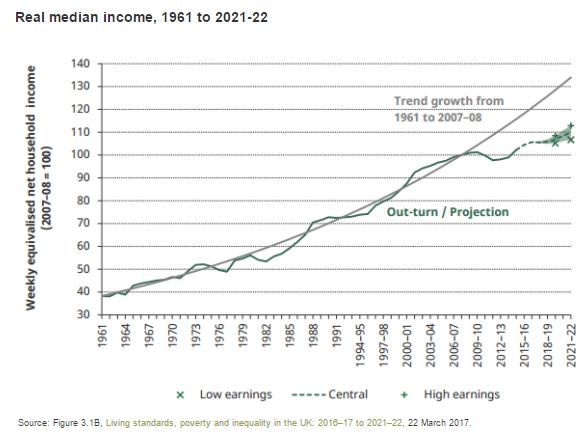

Brexit The economic environment couldn’t have been better for Labour:

unlike 2015 we had falling real wages and the slowest quarterly GDP growth rate in the EU. Labour’s manifesto held out hope, while the

Conservative manifesto was a liability. Despite all this, the Conservative vote share was above Labour.

What the election

does show beyond doubt is that the attitudes most of the PLP had

towards the Left, which they had carried with them from the 1980s, are no

longer appropriate. The result was not the disaster they had been so

sure would happen. That showed some left wing policies can be very

popular, even if they are called anti-capitalist by those on the

right. The curse of austerity on the UK electorate has lifted. Unlike

the ‘dementia tax’, none of the policies in Labour’s manifesto

proved to be a millstone around Corbyn’s neck. The days when Labour

politicians needed to worry about headlines in the Mail or Sun are

over.

The big lessons of

the last two years are for Labour’s centre and centre-left. The

rules that applied in the 1980s no longer apply. The centre have to

admit that sometimes the Left can get things right (Iraq,

financialisation), and they deserve some respect as a result (and

vice versa of course). The centre and Left have to live with each

other to the extent of allowing someone from the Left to lead the party.

Corbyn has shown that the Left are capable of leading with

centre-left policies, and the electorate will not shun them. With the

new minority government so fragile, it is time for the centre and

centre-left within Labour to bury old hatchets and work with Corbyn’s

leadership.