As the Covid Inquiry progresses, it is clear the government led by Boris Johnson made two catastrophic mistakes during the pandemic of 2020. The first was to do virtually nothing until late March. The second was to encourage a second wave in the autumn, and again fail to take effective action to stem it during the rest of that year. With the first there are potentially many who contributed to that mistake, including our broadcast media. The second mistake was primarily the responsibility of Rishi Sunak and Boris Johnson.

As the second is simpler, I’ll start with that.

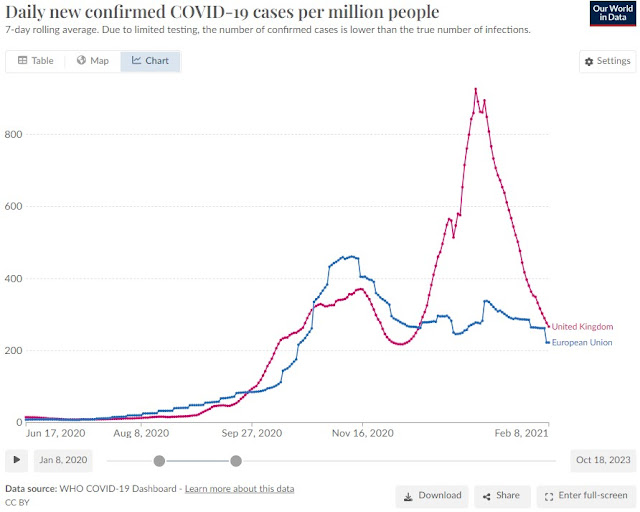

In June the first lockdown continued to be unwound, yet during June and July case numbers remained fairly flat. The reproduction number R was close to one. At the beginning of August Sunak introduced the ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ scheme, encouraging people to eat inside restaurants. That was not the only reason cases began to rise in August and September, but the evidence is clear that it helped. The current chief scientific adviser, Angela McLean, called Sunak Dr Death in one message. Incredibly SAGE, the government’s scientific advisers for the pandemic, were not consulted about the scheme. Here is one of its members, John Edmunds, describing to the inquiry his anger.

In September SAGE recommended a new lockdown to prevent “a very large epidemic with catastrophic consequences in terms of direct Covid-related deaths and the ability of the health service to meet needs.” Johnson, encouraged by Sunak, rejected that advice. Through September and October more minor, regionally based restrictions were imposed, but as the data shows clearly this failed to avoid a rapid rise in case numbers. At the end of October the crisis was so bad that Johnson was forced to impose a national lockdown. As the data also shows, cases started falling after the inevitable lag. Lockdowns clearly work in saving lives, but Johnson had resisted the recommendations of his scientific advisers for weeks before imposing one.

Worse was to come. This national lockdown ended at the beginning of December, even though case levels remained high. Cases started rising again soon afterwards, but Johnson was determined to avoid a national lockdown over Christmas. The third national lockdown began on 6th January, and once again it produced a rapid decline in cases, but only from a horrendously high level.

Not only do lockdowns work in saving lives in the short term, as they inevitably must because they reduce social interaction, but they also save lives in the long term if effective vaccines are developed. That this statement is not blindingly obvious to everyone is a testament to motivated beliefs. In the Autumn and Winter of 2020 it was clear there were good chances of a vaccine being developed. As a result, tens of thousands of UK citizens who died as a result of Covid during this period did so as a result of Johnson and Sunak ignoring expert advice. Outside of wars, other political mistakes don’t even get close to being as serious as this.

The earlier catastrophic mistake, doing nothing as the pandemic unfolded until mid-March, shares some similarities but there are important differences. The key difference is knowledge. In the Autumn nearly all experts, inside and outside of government, knew how the virus behaved and what was needed to control case numbers until a vaccine arrived. Johnson and Sunak went against this scientific consensus. This was less so in January, February and early March 2020 because much less was known.

This lack of knowledge was compounded by pre-pandemic planning, which had focused on a flu outbreak that was different in nature to Covid. Focusing on just one type of pandemic, rather than a range of possibilities, was an error that cannot be put at the feet of political leaders in 2020. Equally the degradation of the PPE stockpile, which led to the deaths of doctors and nurses during the early months of the pandemic, was mainly a consequence of the decisions of previous Conservative political leaders.

However, from the evidence I have seen, it is clear that ministers, and in particular the Prime Minister, were from the outset predisposed against taking large scale preventative measures. Herd Immunity, as the strategy became known, is really just a name for doing nothing unusual in a pandemic. As is often the case with ideologically led rather than evidence led governments, the rationale behind this strategy evolved not from evidence or from example (what other countries were doing), but from the need to support this predisposition.

A good example of this was the idea of behavioural fatigue: lockdowns could not be imposed because people would quickly tire of restrictions and the lockdowns would become ineffective. It is not clear where this idea came from, but it seems it was not from the behavioural experts who were part of SAGE or its sub-committees. As Christina Pagel notes here, the reality was the opposite, with 97% of people complying with the rules in the first lockdown. Trust only began to break down when the members of the government got caught breaking the rules.

Because the initial policy was not evidence led, the government made little attempt to talk directly to its own experts, or involve them in the decision making process. Professor Neil Ferguson talked of a “Chinese wall” between the experts on SAGE and the officials preparing for the pandemic. In early March “both John Edmunds and myself got concerned about the slight air of unreality of some of the discussions, and started talking in the margins to government attendees, saying: ‘Do you know what this is going to be like?’” Ferguson said.

It was in part these efforts, rather than the sea-change in the science that politicians and the media talked about, which led to the eventual imposition of lockdown. But it took some time to persuade Johnson that he needed to change his approach, and that two or three week delay led to tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths.

If Johnson’s predisposition against lockdowns is largely the cause of tens of thousands of unnecessary deaths in 2020, the broadcast media also failed badly in the early months of the pandemic. As a recent study by Greg Philo and Mike Berry shows, in those initial months the broadcast media largely became a mouthpiece for the government, with information about the pandemic mostly coming from senior political correspondents.

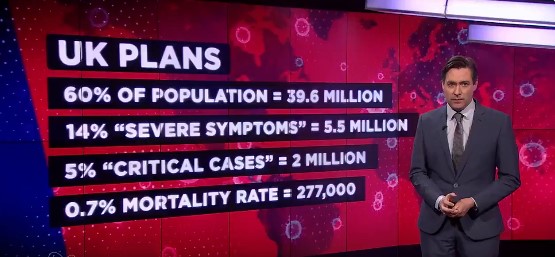

Above is a still from this clip from Irish TV from mid-March. As Richard Horton pointed out, the small amount of information required to do calculations of this kind had been available from studies published in the Lancet in January and February. As he put it, “any numerate school student could make the calculation”. Did no journalists from the MSM think to try to do similar assessments before mid-March, or just talk to experts outside government who could do so more easily? If they had, surely they would have realised that two million critical cases was way beyond what the NHS could handle?

If just one MSM journalist had done something like this before mid-March, it would have been something other journalists could have referenced when talking to officials and ministers. That, in turn, might have made ministers realise what the SAGE modellers later got them to understand. Each week’s delay in imposing a lockdown cost countless lives. Our broadcast media’s fondness of Westminster access and its aversion to talking to experts is also partly to blame for the mistakes government ministers made at the start of the pandemic.

Politicians and organisations are bound to make mistakes, as they are not superhuman. However I think there is an important distinction between mistakes where politicians or organisations act on or in accordance with expert or received wisdom, and mistakes where they ignored or went against that wisdom. In the first case the responsibility is shared, but in the second it rests with the politicians or organisations alone. When the advice and knowledge of the consensus of experts is ignored in a pandemic, and tens of thousands of people die unnecessarily as a result, then responsibility for those deaths lies squarely with the politicians and media organisations that ignored that consensus.