The UK is currently suffering a level of strike action not seen for decades. There is a simple reason for most of that - it is government policy. Take the continuing strikes in the rail industry. According to the Financial Times two weeks ago: “Employers had planned to offer a 10 per cent pay rise over two years to the RMT union, but were blocked by the government, which controls the industry’s finances, according to three people familiar with the matter” by adding tough new conditions at the last minute.

Or take the unprecedented strike by many nurses. Nurses have seen a large cut in their pay relative to those in the private sector since 2010. The government’s current pay offer will see that continue. Quite simply, nurses are being forced to strike because the government insists on reducing their standard of living compared to private sector workers as well as making their working conditions more intolerable. Now if for every nursing vacancy there were hundreds of applications then you could make a case for lower pay, but the opposite is true, partly because many nurses are leaving the NHS. It is a similar picture across the public sector.

Of course the government tries to assert that none of this is true. Instead they like to pretend that they are on the side of poor suffering Joe Public, and also like to claim that somehow it is the Labour opposition’s fault that we are seeing all these strikes. Given the level of misinformation we have in this country many (although for nurses certainly not a majority) will believe them. The reality is that the government thinks these strikes will work to their political advantage in returning some core Conservative support they have lost in recent months. In other words, they are making these strikes happen, despite the inconvenience this will cause and the damage it will do to the country, because they believe it’s to their party's political advantage.

Governing in a way that harms the country but boosts your flagging popularity is a good measure of political and moral bankruptcy.

But strikes are not an isolated example in an otherwise sea of policies the government is enacting to benefit the country. Take one of the most pressing issues of the moment, which is the crisis in the NHS. UK citizens are dying who would otherwise have lived because ambulance waiting times have sky-rocketed, A&E departments are overloaded and delays for many basic operations are at record levels. A key reason for this is a lack of beds and infrastructure, made acute by the number of patients being treated in hospitals with Covid, together with an inability to pass on patients to social care

Neither is an excuse for the government to do nothing! On the contrary, dealing with both is what any government is there to do. But where is the government action to create more NHS beds, and the staff that goes with them, following the emergence of Covid? What are the government’s plans to deal with the crisis in social care? Once again, by refusing to pay NHS staff more, and failing to provide the resources to attract more people into social care, the government is actively making things worse.

The new Prime Minister made a big speech announcing a new policy last week. But it wasn’t about the NHS or social care, or the growing poverty caused by the cost of living crisis. Instead it was about people crossing the Channel in small boats, mostly to claim asylum in the UK. Shortly afterwards some died trying to make that crossing in icy waters. Yet, as Lewis Goodall points out in this excellent summary, Sunak’s speech did not contain the one policy that could solve the problem of small boat crossings at a stroke, which is for the government to provide a means for asylum seekers from wherever they come to claim asylum safely.

Once again, the problem of Channel crossings is a problem of the government’s own making. By failing to provide any safe route for asylum seekers from all but a few countries to claim asylum in the UK, they create the demand for small boat crossings and the smuggler gangs that facilitate this. Why don’t they want to provide a safe route for asylum seekers? Because they want less asylum seekers in the UK compared to most other comparable countries. While some countries that have the same goal erect high barbed wire fences on their borders, we have the English Channel.

Those in the Conservative party, if they were being honest, would say they were just doing what their supporters want. Those in the Labour party who do not point out the truth about Channel crossings would say the same about the voters they need to attract to win the next election. There is some logic for such claims, because the UK’s FPTP voting system and our right wing press bias policy towards the interests of those who just want less people claiming asylum in the UK. But if this is the politicians’ excuse, why lie about it, and call those making the Channel Crossing ‘illegal migrants’? It means politicians are going beyond what they need to do to represent these voters. They are not only helping to put people’s lives at risk just for party political gain, but they are distorting or concealing the truth from those they represent. [1]

Take the biggest crisis facing the world today, climate change. What does the current government do? Opens a new coal mine. A government that lets people die just to win votes, or puts the future of humanity at risk for a bit more money today, is a good indication of political and moral bankruptcy.

It seems the government has given up on the business of governing, and instead its actions are determined only by what gains their party a few more votes. You might be cynical and say it is ever thus, but I think this is wrong. Whatever you might have thought about her vision, Margaret Thatcher did have ideas about how to make the UK a better place. Some of that might have been destructive, like reducing union power, but it was also constructive, like helping to create the Single Market for EU trade. There were of course some policies designed just to win votes, like selling council houses for example, but there was also a clear set of new ideas about how to improve the economy and individual opportunity.

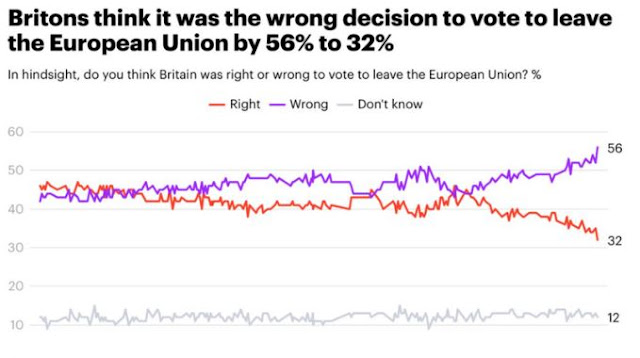

The same is true for the Labour government of 1997-2010. Gordon Brown could list the many ways it had made lives better through specific policies in a conference speech. It too had a vision. If we call the vision of Thatcher neoliberalism, we could call Labour’s vision neoliberalism with a human face. Yet it is hard to imagine Rishi Sunak giving a similar speech about the achievements of Conservative led government since 2010. Austerity left the UK permanently poorer, put UK public services in a dire state, and yet UK taxes are at a record high. Brexit has bought further economic misery but hasn’t brought any benefits worth listing in a conference speech, with even immigration at record highs.

To describe all three governments as embodying neoliberalism misses these key differences, and therefore misses the political and moral bankruptcy of the current government. Yes, it still spouts neoliberal platitudes, but they have increasingly become clichés designed not to try and make the country better off with more opportunities for its citizens, but instead used as a mask for funneling money to friends, donors or potential future employers. So the UK’s private water companies are protected at the expense of sewage in our rivers and on our beaches. Energy companies are allowed to keep their record profits if they invest in producing more climate warming oil. Private companies with the right political connections are paid over the odds with public money to provide unusable PPE, then paid with public money to store it and then other private companies are paid with public money to dispose of it. I have described all this as a transition from neoliberalism to a form of plutocracy elsewhere.

Once we see austerity as the huge mistake it undoubtedly was, we can see that the bankruptcy of the current government did not start after a referendum in 2016, but from its very start in 2010. Wanting less public services and taxes without changing what the public sector does turned out to be as foolish as it sounds. With this, and nonsense like Britannia Unchained, Conservative ministers took the platitudes of neoliberalism [2] and thought that together they made a coherent and realistic vision, yet they remain in denial that this pursuit has done nothing but harm to the UK economy.

All this represents an intellectual as well as a political and moral failure. A failure to see that growth under Labour before the financial crisis matched that under Thatcher, and also more than matched growth in other G7 countries, yet with better public services and without the advantages of growing North Sea Oil revenues. A failure to recognise that increasing taxes to bring NHS spending up to European levels was popular. A failure to learn from the fact that the Global Financial Crisis reflected a lack rather than an excess of government regulation. All these showed at the very least the limitations and dangers of unbridled neoliberalism, yet these lessons were ignored

This intellectual failure didn’t end once the Conservatives were in power. After unjustly blaming, with the invaluable help of their press, immigrants for many of society's problems in opposition, Cameron set up immigration targets he either couldn’t hit or wasn’t willing to hit, yet his party used immigrants as a scapegoat for the effects of austerity. This played into the hands of populist Brexiters, who only had to link immigration to free-movement to make their case. After Brexit it seemed that the exclusive motivation of Conservative MPs became power for power’s sake, exemplified by the election of Boris Johnson. His own moral bankruptcy does not need retelling, although it is worth noting that public money is still being used to defend his lies over Covid partying.

When a government refuses to use our money to pay nurses a decent wage or relieve severe rationing in the health service, but instead spends it on defending the obvious lies of a disgraced former party leader, that is a pretty clear sign of political and moral bankruptcy.

It is true that the Covid pandemic would severely test any government. But the current government, including the current Prime Minister, failed that test repeatedly. Long term planning for a pandemic in the form of stockpiles of equipment was allowed to become useless under austerity. Once the pandemic started, an initial hope that the pandemic could just be ignored led to little contingency planning, yet that hope was scuppered once data arrived. Over the summer of 2020 Sunak championed spending public money that helped create a second wave of infection, and pushed Johnson to listen to a tiny minority of experts who were against lockdowns. Johnson himself, under the influence of some newspaper owners, began to distrust the centuries old methods of dealing with pandemics, so scientific advice was frequently ignored and lockdowns delayed. Tens of thousands died unnecessarily as a result.

If there is one image that sums up the moral bankruptcy of the current Conservative party for me, it is the massed ranks of Conservative MPs in the summer of 2021 sitting on the crowded government benches with hardly a face mask to be seen, even though the government’s own advice at the time was to wear masks in crowded indoor places. It was just like partying in No.10, except it involved nearly all Conservative MPs in an unashamedly public way. Here were our elected representatives putting their own personal convenience, vanity or warped ideology above the interests of those around them, and by implication above the interests of those they represented. The Conservatives have been labelled the nasty party with much justification, but since 2010 they have become a party whose only aim seems to be to look after themselves.

[1] At the end of the day it’s a policy that makes a minority suffer, and a few die, so that some voters can feel happier. The primary responsibility for those policies lies with the politicians that enact them.

[2] For example 'government should get out of the way', reward the 'wealth creators', or 'regulations hold back business'.