Paul Krugman once said that to improve a country’s standard of living over time “productivity isn't everything, but, in the long run, it is almost everything”. I want to use a recent Resolution Foundation study to examine a slightly different question, which is what determines differences in prosperity across countries. The answer is very similar, but with an important modification.

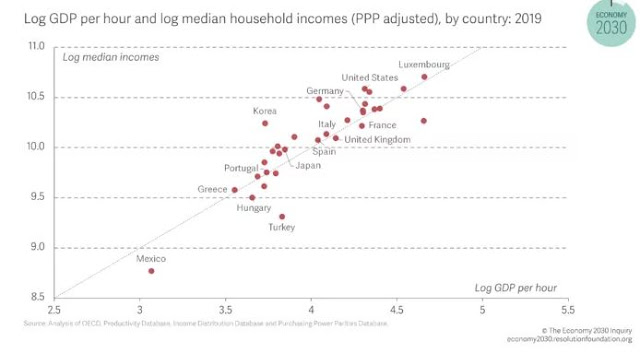

The Resolution Foundation report by Krishan Shah and Gregory Thwaites compares productivity and (PPP adjusted) incomes per household in the UK with the US, Germany and France, and with France it looks at both 2008 and 2019 so we can look at the comparison over time. But it starts with the following chart which includes many more countries.

This plots GDP per hour (productivity) on the horizontal axis against median income (both logged) for a number of countries. The line passing through the points is the 45 degree line, and the fact that the points are clustered around this line shows that differences in productivity are crucially important. However there are big divergences from that line, suggesting other factors are important.

The first key point, which can get lost in the detail of the report, is that incomes are not the same as prosperity, if you define prosperity in a more general sense. Three of the most important aspects of prosperity that are not captured by incomes are leisure, public goods and investment. Consider each in turn.

Imagine two countries. In one, people work long hours, have few holidays and have a long working life, and as a result their incomes are high. In another, people work less hours, have longer holidays and retire earlier, and their incomes are less as a result. It would clearly be a mistake to call the country where people work more hours a more prosperous country. We could ask the same question where incomes differ because of different levels of tax, where tax goes to pay for more public goods. The country where incomes are higher but less goods are provided by the state is not necessarily more prosperous, particularly if private sector provision of these goods is less efficient (think US healthcare). These are key issues when comparing the US and France, for example.

The final point is that you could raise incomes by not investing in the future. As future productivity depends on investment today, this might raise people’s incomes today, but at the expense of their incomes tomorrow. Differences in investment may occur not just in producing more capital goods, buildings etc, but also with investment in education, or simply in terms of income from overseas assets.

These factors are important to consider when we look at the relationship between comparisons of productivity and comparisons of income per household. Here is the report’s comparison between the UK and France in 2019.

On the left we have GDP/hour worked, a measure of productivity [1]. That shows that France is 17% more productive than the UK. The penultimate column is average household income, where France and the UK are almost equal. Why is France more productive but incomes are no higher? The main answer is the ‘worker/population’ column, which in this case mainly reflects earlier retirement in France (but also longer life expectancy). Does that mean that the average French person is not more prosperous than the average person in the UK, despite being more productive? Almost certainly [2] not, because people in France have decided to use their greater productivity to retire earlier.

Differences in the proportion of workers to the population doesn’t just reflect retirement. There are fewer young people in the workforce in France. This is partly an investment effect (more education) but also reflects high youth unemployment. The other big factor reducing average incomes in France is the ratio of domestic household income to national domestic income. This partly reflects the fact that French firms invest more so the share of profits in GDP is higher (and the wage share lower), but it also reflects higher taxes and (almost certainly) therefore more public goods. [3]

I hope it is now clear why I wanted to stress the distinction between incomes and prosperity. Although average incomes in France may be no higher than in the UK, the French are still more prosperous because they have used their productivity advantage to have a longer retirement, have more public goods and to invest more in the future. So productivity remains crucial to prosperity, but how people enjoy that prosperity can be quite different between countries.

A final but crucial point comes from comparing the last two columns. Median income is the income of the person in the middle of the income distribution, where you have as much chance of having an income above or below that level. If the distribution of income is very unequal, and in particular if it is skewed in favour of those at the top, median income will be below average income. Median incomes are significantly higher in France than in the UK, because the UK is more unequal. So although productivity is crucial in making cross country comparisons of prosperity, inequality is also important. (For a more detailed comparative analysis of different income brackets, see John Burn-Murdoch here. For a discussion of the impact of changes in the proportion of income taken by the top 1% in the UK over time, see here and particularly here.)

The comparison for 2008 rather than 2019 illustrates a key point that is familiar. While the productivity gap in 2019 was 17%, it was only 7% in 2009. The last 10/15 years really has been a period of UK decline. The 2019 comparison with Germany throws up similarities and differences to France that the report goes into. While the productivity gap is similar, the benefits are taken in terms of working less hours rather than less years. Turning to the US, the productivity gap with the UK is similar to the gap with Germany and France, but US income is much higher. Some of that big gap is because workers in the US work more hours, and taxes are lower because public good provision is lower, but there are also differences that must reflect problems with the data used.

This analysis by the Resolution Foundation illustrates two general points. First, comparisons of personal (post-tax) income levels are a partial indicator of relative prosperity, because they ignore leisure, investment and public goods. For that reason, a comparison of productivity levels may be a better indicator of comparative prosperity than relative income levels. Second, what productivity ignores is the often significant impact different levels of inequality can have on the prosperity of the typical household.

[1] GDP/hour worked is a very aggregate measure of productivity, and could reflect different compositions of output as well as how productive similar firms are.

[2] We could drop the almost if we could be sure that the difference in retirement ages represented national preferences, including choices about retirement incomes.

[3] In theory higher profits could reflect higher dividends rather than higher investment, of course. This links to the decoupling debate (between productivity and real wages) I talked about here, based on work by Teichgräber and Van Reenen.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Unfortunately because of spam with embedded links (which then flag up warnings about the whole site on some browsers), I have to personally moderate all comments. As a result, your comment may not appear for some time. In addition, I cannot publish comments with links to websites because it takes too much time to check whether these sites are legitimate.