Interest rates have increased twice in the UK and the Fed has signaled increases to come. To some the reason for this might seem obvious. Inflation is 7% in the US and expected to be over 7% in the UK by April. Surely the job of interest rate setting central banks is to use higher rates to control inflation? While it is not as simple as this, the fact that some people think it is can weigh heavily on monetary policy decision makers.

In reality that is not the central bank’s job for two reasons. First, sometimes the economy is hit by temporary shocks, like higher energy prices, which will only raise inflation for a year or two. Second, it takes time (2 years?) for the full effects of higher interest rates to impact inflation, and it works mainly by depressing output. Put the two together, and raising rates following temporary shocks would do little to reduce the size of those shocks, and instead would reduce inflation just as it was coming down anyway. More importantly, it would lead to pointless instability in output, incomes and unemployment.

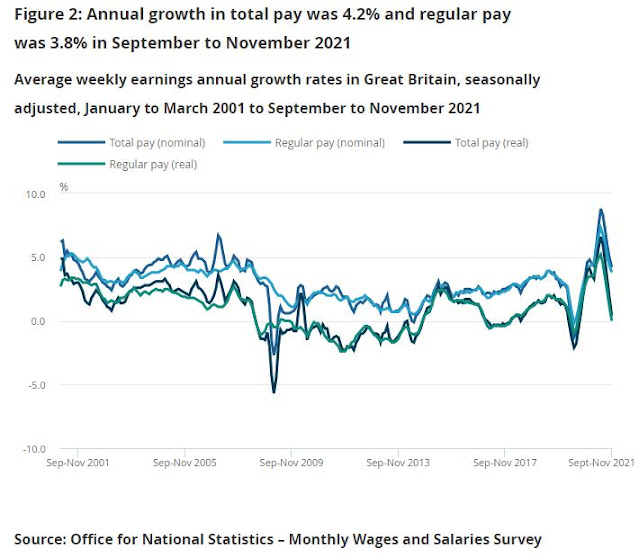

Crudely, this was the view of central banks in 2021 as inflation began to rise. So what has changed in 2022 in the US and UK? The answer, for those in the US, was not fiscal stimulus, because the bounce in inflation has been pretty similar in character across the G7 [1]. Instead, I believe, it is earnings growth in the context of a tight labour market produced by the recovery from the pandemic that is worrying central bankers. Here are two charts, for the US and UK. Source US, UK.

How should we interpret these charts? If we are thinking about how domestic inflation is likely to develop, looking at real wages (the spending power of wages) as shown in the UK chart is the wrong measure. Instead we should look at nominal wage growth, subtract likely underlying productivity growth (because wages should get the benefit of productivity growth), and see if that is above or below the inflation target of 2%.

Unfortunately what underlying productivity growth will be after the pandemic is not known for certain. But in the UK the Bank of England is expecting productivity growth of about 1% a year. That means wage inflation of 3% a year is not inflationary, but pay increases at the end of last year were significantly higher than this, and the Bank’s agents suggest firms are planning wage increases in the 4+% range. That would be inconsistent with the Bank’s inflation target of 2%. US forecast productivity may be slightly higher than 1%, but very recent numbers for both the Atlanta Fed’s tracker above and the EPI wage tracker suggest wage increases are running at an inflation target busting level.

This was why the Governor of the Bank of England took the unusual step last week (as the MPC raised rates to 0.5%) of appealing for wage restraint (more below). The background behind higher wage increases is a tight labour market as output finishes its recovery from the pandemic. The reason for the tight labour market in the UK is not buoyant demand (the UK has only just reached pre-pandemic activity levels) but a withdrawal of a large number of workers from the labour market compared to pre-pandemic levels. Demand is higher in the US, but the same phenomenon is happening there. There are theories why this is happening, but little strong evidence.

The tight labour market is why this episode is so different from 2011, when the ECB raised rates following higher commodity prices but the Fed and BoE didn’t (just). Then there was widespread unemployment, so no risk that wage inflation would rise. In that episode the ECB ended up looking very foolish. Today is more like the period between 2004-7, when oil prices rose slowly but substantially, and UK and US interest rates rose significantly.

But, but, but, you might say, the purchasing power of wages are falling a lot! Surely it is reasonable for workers to have higher wage increases in these circumstances? Unfortunately, to the extent that the higher fuel and food prices are permanently higher, you have to first answer this question: who ultimately pays for higher food and energy prices? Replying “someone else” is not a good answer, because it leads to exactly what these central banks want to avoid, which is a wage price spiral as workers and firms try to pass on these higher costs to each other.

While the economic logic of this is sound, the politics are not, which is why the Governor’s remarks on wage settlements were badly judged. Telling people their living standards must fall by even more because of higher energy prices and ignoring what is happening to, for example, the profits of energy companies is just asking for trouble. The governor of the Bank of England should appear even handed on such sensitive issues, and not single out wages for special pleading.

There are two major reasons why raising rates rapidly might be a major mistake, particularly in the UK where the recovery in the economy since the pandemic is much weaker than the US. The first risk is that the recent increase in earnings turns out to be short-lived of its own accord. The annualised three month wage inflation data (HT @BruceReuters) for the UK gives a hint of that. The Bank is placing a lot of weight on their agent surveys. Wage inflation could tail off because those who have withdrawn from the labour market could be enticed back in by the higher wages we have already seen. In addition, if the Omicron wave dies down (as seems likely as we move away from winter) will firms be able to utilise their existing workforce more effectively, negating the need for higher wages to attract staff?

The second risk is the impact on the economy. Again the UK is particularly vulnerable, as no fiscal major stimulus has or will take place during the pandemic recovery period. There are already plenty of forces dragging demand down, You can see the problem for the UK in the Bank’s own forecasts. In its central forecast, with rates continuing to rise and energy prices staying high, the Bank expects inflation to overshoot its target, falling to 1.5% in 2025Q1 (the end of their published forecast), with rising unemployment and demand less than supply. In contrast with rates staying at 0.5%, inflation comes down to target in 2025Q1. So why go further than 0.5%, as some MPC members wanted last week? In addition, if energy prices start falling as the market expects, inflation will be lower sooner.

To cut a long story short, if rates continue to rise we may find the Bank in a year or two’s time cutting rates as quickly as they are expected to raise rates this year, in the context of a very gloomy outlook for the UK economy. Activity is more bouyant in the US, but similar risks apply there, with the additional political costs of bringing an anti-democratic political party into power. Worse still, if central banks are slow to reduce rates, in the context of a huge hit to personal incomes, we could be talking about a new recession that UK and/or US central banks have contributed to.

So what might at first appear to be an inevitable rise in interest rates following a large inflationary shock, in fact represents a big gamble by central banks that could backfire badly.

[1] As I have suggested before, that fiscal stimulus may have raised US inflation earlier and slightly more than elsewhere, but as it is likely to be temporary if the pandemic unwinds, it seems a price well worth paying for a recovery that is up to 4% of GDP stronger in the US.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Unfortunately because of spam with embedded links (which then flag up warnings about the whole site on some browsers), I have to personally moderate all comments. As a result, your comment may not appear for some time. In addition, I cannot publish comments with links to websites because it takes too much time to check whether these sites are legitimate.