Before getting distracted by the spin put on Friday’s budget, it is important to be clear what the motivation for it is. It’s not a budget for growth, it’s a budget for the rich and those who fund the Conservative party. Abolishing the 45% tax band obviously benefits only the very well off, dropping the increase in corporation tax will mainly benefit shareholders who are mostly at the top of the income distribution, not extending the windfall tax on energy producers will exclusively benefit shareholders, not increasing NI rates benefit the better off far more than anyone else, ending the cap on bankers bonuses benefits the already very rich, and so on. Conservative MPs are much more right wing on economics than Conservative voters or even party members, and this is a budget for them, as long as it doesn’t mean they lose their jobs.

The Resolution Foundation calculates that almost two thirds of the tax gains go to the richest fifth of the population, with almost half going to the top 5%. They also point out that the stamp duty changes mainly benefit richer households in the South East. Of course poorer households will get a small amount of this giveaway, but less than is needed to cover the increased costs of essentials according to NEF. The IFS have looked at all the forthcoming tax changes (including frozen income tax allowances), and they calculate that your income would have to exceed £155,000 before you are better off, and if you earn a million a year you gain £40,000

It is also a budget that is highly likely to mean cuts in public spending after the next election. The OBR were not allowed to publish their post-budget forecast, for the first time in their 12 year existence, because if they had been their budget deficit projections would have shouted ‘not sustainable’. Not sustainable is just a shorthand way of saying that taxes will have to rise or spending will have to be cut, unless something very beneficial for the public finances turns up. But of course it’s equally likely that something detrimental to the public finances will turn up. You don’t get to announce the biggest tax cut for 50 years in a deteriorating economic climate without severe implications for future spending.

Here are the Resolution Foundation’s assessment of the deficit and debt, and here is the assessment by the IFS. Both suggest deficits in the medium term that are unsustainable. The new Chancellor also committed himself to reducing government debt relative to GDP in the medium term, meaning that if these deficit projections turn out to be even roughly right he is going to have to raise taxes or cut spending.

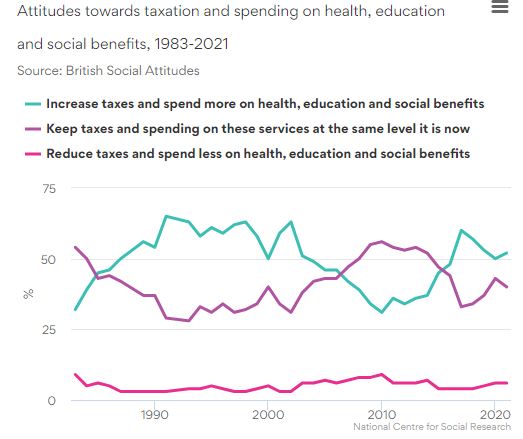

It cannot be stressed often enough that cutting taxes and spending less is a very unpopular policy to pursue, unless you are a Conservative party member or a large part of the commentariat. This is from the latest British Social Attitudes survey.

Just 6% of the population want lower taxes and lower spending on health, education and welfare, while 52% want the opposite.

So to the spin. What the government would like you to think is that this is about fairness vs growth. These measures are very unfair, but they say they are designed to increase long run growth so everyone will be better off (just the rich will be a lot better off than the poor). The spin, like the deficit spin that these same politicians lectured us with for the last 12 years but have now abandoned, is a load of nonsense. There is no relationship between tax levels and prosperity. Worse still, as I outlined here, the evidence clearly suggests that increasing inequality at the top reduces growth. Either the government is blind to the evidence, or they have to pretend it’s all about growth as a cover for the true reason for tax breaks for the rich: their ideology and party donors.

If this government really wanted to increase growth it would make trade with the EU easier, but right now it is doing the opposite. It would be focusing only on encouraging the energy of the future, green energy, which is now much cheaper than gas, Instead they are encouraging fracking (and saying you shouldn’t worry about small earthquakes) and more investment in getting oil out of the North Sea. If this government really wanted to increase growth, it would be helping the NHS reduce the number of people not working because they are sick by training more nurses and doctors and paying them more. Instead tax cuts now mean that in the future the NHS, with its record waiting lists, will be even worse than it is now, if it has a future at all.

If you (erroneously) think the markets know more about growth than researchers who examine the evidence at the IMF, then they too think the government is doing nothing for growth. If the markets believed this budget would increase long run growth, sterling would appreciate. Instead the uncertainty created by an unfunded tax giveaway for the better off has led to the cost of government borrowing rising substantially both just before and following the budget, and sterling has fallen against the Euro. (The latter is particularly significant, as you would normally expect an unfunded tax giveaway to appreciate sterling because of expectations of higher interest rates.)

Some of the criticism of this budget is also missing the point. It's very unlikely we will see a repeat of the Barber boom of the 1970s for two reasons. First and most importantly because we now have an independent Bank of England. Instead what this budget ensures is higher interest rates. (Can there be much doubt that if it was Kwarteng rather than the Bank that decided interest rates, then a short term inflationary boom would be a bigger possibility.) But as I noted in my last post, offsetting a short term inflationary boom with higher interest rate is not a precise art, so there is a possibility that the government might get lucky with three or six months of 2.5% annualised growth (or more) before the next election. The second reason we will not get anything like a Barber boom is that most of the tax cuts are going to the better off who save most of their extra money.

What has to be added is what was absent from this budget giveaway. There was only the smallest additional help beyond the price cap for those struggling to make ends meet, and instead more use of sanctions for claimants, sanctions which the government’s own research says caused more harm than good so they refused to publish it. Alongside higher energy prices, we have sharply higher food prices which the government is ignoring. It is indicative of where this government’s priorities are that their first fiscal actions have focused on giving the most money not to those who need it most, but those who need it least.

Why was this a uniquely awful budget, that led to higher government borrowing costs and a falling currency. Tax cuts aimed at the wealthy at a time when many less wealthy are finding it hard to make ends meet is pretty bad, but it is not unique in recent times. George Osborne cut the top rate of tax in 2012 in the middle of a sustained period of austerity, and cut corporation tax too. Nor is justifying tax cuts aimed largely at the rich by pretending they will boost long term growth a new excuse. Trickle-down economics has been growing as part of Conservative DNA since Thatcher. The growing evidence that it doesn’t work and will probably reduce growth has little chance when set beside growing party donations from the very rich.

What made this budget stand out from any UK budget over the last 30 years was the absence of any attempt to match taxes to day to day spending over the medium term. I’m not talking about the deficit fetishism of Osborne, Hammond and Sunak: that had long passed its sell by date. However for the last thirty years Chancellors have attempted to put their decisions within some kind of overall fiscal framework. Kwarteng not only failed to do that, but he stopped the OBR making that clear. That matters not just because it raised borrowing costs and depreciated sterling, but because it almost certainly means, if this government remains in power, spending cuts on the horizon. Cuts in spending that will be far deeper than anything George Osborne did, because UK public service provision is already at rock bottom and in some cases close to collapse.

When the mainstream media and non-partisan think tanks talk about this budget being a big gamble, they are going as far as they feel they can in condemning it. What the country and the economy needs right now is reducing the record delays for standard NHS treatments, reducing appalling waiting times for ambulances and A&E, allowing schools to fill the gaps left by the pandemic rather than not replacing teachers to pay energy bills, and so on. An economy where the public sector no longer works is an economy that no longer works. What this budget showed is a Chancellor who not only doesn’t understand this, but intends to make it worse.