This post is prompted by the discussion around the Autumn Statement, but also in particular a post by Ian Mulheirn. Here is the key diagram from his post.

I think the diagram is useful because it distinguishes three aspects of aggregate fiscal policy that can easily become confused. However it is worth talking a bit about its limitations lest the diagram itself adds to confusion.

Each of the three circles above represents a non-central point on a spectrum. Take the ‘support short term growth’ for example. At one extreme (near to my own position [1]) you can believe that in a recession, or before an expected recession, or during the recovery from a recession, the need to stimulate the economy should take absolute priority over all other objectives. The other extreme would be to ignore the macroeconomic situation entirely, which Osborne/Cameron in 2010. There are plenty of intermediate positions between those two extremes, like Balls/Miliband over the same period.

The same is true for public services. I would go further and make a conceptual distinction between what you might call the ‘scope of the state’ and ‘how well the existing state is funded’. These both have to be continuums. My own view on the latter is that we are currently not even at an extreme point, but one which is not tenable.

What does fiscally conservative mean? I think the label here is misleading, because fiscal conservatism could equally be the label for the other circles. In my view the issue here is about the expected path of public debt, or public sector net wealth, over the long run. One extreme on this would be that public debt doesn’t matter at all. The other might be that debt should be reduced rapidly, and there are plenty of intermediate positions between these two extremes. Any good medium term current deficit fiscal rule will have to make a choice about where on this continuum it wants to go.

I would not include under this heading debates about the form of fiscal rules. This debate is more technical in nature, and involves whether it is better to target the current deficit or the total deficit, or whether some particular change in the debt/GDP ratio is a good target, and so on. Discussion often confuses the form of a target with the value it is set at. For example, a target for the medium term current deficit is a good rule in my view, but there is still a debate about what level the target should be at, and that will depend on how quickly public debt should fall or rise in the long run.

Making these distinctions help us see historical events in a clearer light. 2010 austerity, for example, combined two of these circles: a large contraction of public services, and ignoring the need for fiscal stimulus in a recession. It is also interesting to note that the level of taxes is influenced by at least two of these aspects of fiscal policy: higher public spending implies higher taxes, as does (for given public spending) a more conservative debt policy.

The correct way to locate past Chancellors in all three dimensions of fiscal policy would be a three dimensional chart, with the three axes being ‘how high is public spending’, ‘the priority given to the macroeconomy during economic downturns’, and ‘how quickly should debt rise or fall over the long run’. But three dimensional diagrams are not easy to look at, which is why I suspect Ian uses the simpler formulation above. But that also creates problems.

While I have no problem with the classification of Osborne/Cameron, you could question whether Balls/Miliband were suggesting higher public spending or just less cuts than Osborne. Equally by putting Johnson/Sunak in the higher public spending circle, it’s clear that Ian is taking a conservative definition of ‘higher’. With Hunt/Sunak a budget that back loaded spending cuts and immediate energy subsidies could be spun as worrying about the economy in the short run, but they are still putting up taxes in a recession. I suspect the real reason that spending cuts have been delayed is not the coming recession but just that spending cannot be cut further, and the real reason for energy subsidies is political.

I think it’s clearer if we try and use one straight line and a 2D chart

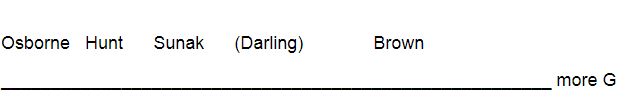

The straight line just looks at the amount of government spending, and I’ve only included actual Chancellors, not PMs or shadows, and excluded Hammond and Javid for space. Brown is out in front for creating an NHS that worked, Sunak (under Johnson) increased spending as a share of GDP in a few public services but not others. Hunt gets to be to the right of Osborne mainly because his spending cuts have not happened yet. (I have put Darling in brackets because his period was dominated by the GFC.)

The second diagram plots the remaining two aspects of fiscal policy. Here I have only included four Chancellors, because Brown didn’t have a recession to deal with as Chancellor, and the GFC blew up his fiscal rules. Darling wins on stimulus in a recession because he did exactly that, while Sunak is next because of furlough. On debt reduction speed Osborne is clearly on top because of what he did once the deficit was brought down, and Darling is where he is because of plans he never got a chance to implement.

I think this is a more informative way to compare what Chancellors did, but it is a lot less pretty than Ian’s original.

I want to end by disagreeing with the main policy point that Ian makes, which is that Labour should aim for the intersection of his three circles. I have no problem with ‘higher government spending’ and ‘stimulus in recessions’. Indeed I think all good governments, from the starting point we are currently in, should increase public spending, and every government should follow basic macroeconomics. Where I differ is on a conservative policy towards public debt.

I understand that in opposition it may make political sense to match the government’s rolling target for falling debt to GDP. But I would hope, once in government, Labour would commission HMT (or the OBR) to do the kind of in depth analysis they did in 1998. This should show the drawbacks of that particular target that I outline here. The most pertinent from Labour’s point of view is that by focusing on debt rather than assets this target discourages the kind of Green investment that is a centrepiece of Labour’s economic policy offering. It is no good hoping these two things don’t conflict based on current forecasts, because at some point they almost certainly will.

Much more difficult is the judgement about the desirable path for net public sector wealth over the long run. Again a good analysis has to look at the costs of getting the judgement wrong. The costs of underfunding public services are today painfully clear. The cost of not reducing the current negative level of net public sector wealth is less clear, once you move beyond nonsense involving market pressure.

[1] I would not argue for immediate fiscal stimulus right now because it could be immediately offset by higher interest rates, but nor would I agree with tax increases. But I am probably at the extreme in believing fiscal stimulus should apply until the recovery from a recession is complete, which is why I think the Biden stimulus was a good idea.

Great summary - sufficiently simple to be understood without being overly simplistic. More like this please

ReplyDelete