One of my (partially) unfulfilled quests is to understand why voters think the Conservatives are better at running the economy, when the objective data suggests they are hopeless at it. A part of the answer is that they use their (greater) airtime much better than Labour, by repeating a few generally misleading lines to take over and over again.

All this week the Prime Minister and ministers have deflected questions about partygate and instead trotted out the ‘real’ successes that Johnson has achieved. Often these are straight lies, but at other times they involve cherry picking statistics. The clearest example of the latter is that the IMF are forecasting the UK to have the most rapid growth among the G7 this year. This is sometimes linked to a claim that Johnson has made the right calls over the pandemic.

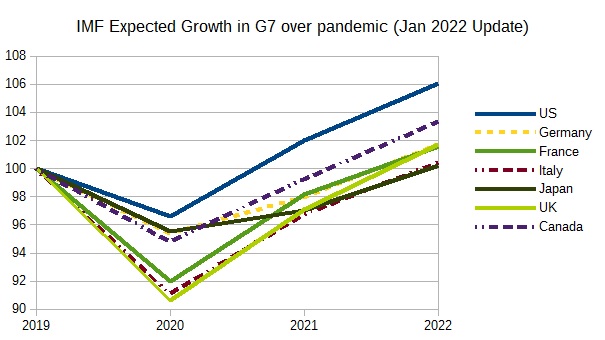

Here is the IMF’s latest projection for growth over the pandemic period, where I have made 2019=100. May contain rounding errors.

It is true that forecast UK growth for 2022 is higher than any of the other G7 countries. But as the chart shows, all that indicates is that we had the biggest recession of all the G7 during the pandemic, and so need faster growth to catch up with pre-pandemic trends. Claiming that faster growth as an indication that the UK made the right calls during the pandemic is clearly ludicrous.

However that is not the point. The point is that ministers and the Prime Minister get away with misleading the public, because these bogus or misleading claims are very rarely picked up in any interview. The technique is simple: make lots of positive claims in an interview about something other than what the interviewer wants to talk about and the interviewer will rarely dispute one, let alone them all. Johnson explains it here.

I first became aware of this technique in the early Cameron years. Conservative ministers when interviewed would always claim that they inherited a deficit at crisis proportions caused by Labour, and therefore they had no choice but to embark on austerity. Then Labour chose not to argue otherwise, and I never saw any interviewer question the claim (which was nonsense on stilts). Together with the right wing press pushing similar nonsense, the result was a large proportion of voters blame Labour for austerity.

Today, Labour politicians understandably talk about the cost of living crisis, but perhaps they are missing a trick here. Voters do not need to be told about the cost of living, but they have much less knowledge about ‘the economy’. They will not bother to check the accuracy of Tory lines to take, and may even think that because these lines go unchallenged they must be true. As a result, the Tory lead on the economy may remain intact. Labour needs to follow the example of the Shadow Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, who in her recent speech explicitly focused on how growth had deteriorated under successive Tory governments since 2010.

Returning to the Chart above, two points stand out. First, the success story among the G7 is the US. Only they appear to have got back to something like where trend growth would be if the pandemic hadn’t happened. The reason was a large fiscal stimulus, and whether that went too far I’ll discuss below. Second, everyone has had a (kind of) V shaped recovery. However with variants appearing just as cases were under control in many countries, I think the vaccines were crucial in getting a V shaped recovery.

Without vaccines, you need regular lockdowns. Even without lockdowns, each new variant spike will mean many consumers withdraw from social consumption (travel, recreation, shopping etc). Vaccines gave people the chance to partially continue social consumption, and largely avoided lockdowns. It therefore allowed an initial recovery to be sustained.

But is the US really the success story the chart above suggests, given current 7% inflation? Did the first Biden stimulus go to far, as some have suggested? The table below is helpful in this respect.

US Real Personal Consumption Expenditures by Type of Product, Quantity Indexes (source)

|

|

2019Q4 |

2020Q2 |

2020Q4 |

2021Q4 |

|

Total |

119.929 |

106.418 |

117.023 |

125.303 |

|

Goods |

131.59 |

128.261 |

141.709 |

151.881 |

|

Services |

114.795 |

97.405 |

106.847 |

114.392 |

Note first that the total hides very different behaviour between consumption of goods and services. Social consumption is concentrated in services, like travel and recreation. Both types of consumption fell in the first COVID wave (2020Q2), but services by much more. From then on, goods consumption grew quickly, largely immune from the impact of later waves of the pandemic. (Durable consumption has grown even faster.) In contrast, service consumption was only just back to pre-pandemic levels at the end of last year, and it will be interesting to see what impact Omicron has in 2022.

In our study of a flu type pandemic ten years before COVID, I assumed exactly this pattern would emerge. What I didn’t assume, which may also have happened, is some displacement of social consumption into durables. As this has been happening worldwide, it is perhaps not surprising that we might be seeing some inflation in specific goods sectors. One final assumption I made, which is not unreasonable, is that inflation would occur just after any pandemic ended as consumers not only increased social consumption to previous trends, but overshot these trends initially to partially make up what they had lost.

We don’t know how much Omicron will suppress social consumption, and whether any new variant waves will be milder or not. At least two scenarios are possible. In the first, COVID variants become more transmissible but milder (with the help of vaccines). If this is the case, expect a return to previous trends in social consumption, with probably a temporary boom as people try and make good a bit of what they lost. That might add additional but temporary pressure to inflation. However demand for goods may plateau or even fall at the same time, relieving some inflationary pressure from that source. The second scenario is that new threatening variants continue for a long time, with vaccines playing catch-up. In that case we may see a medium run shift in the structure of demand away from social consumption.

Rising world fuel and food costs have produced inflation in most advanced economies. US inflation may be the highest because demand there is strongest, revealing both auto supply problems and reflecting expected house prices. All of these things are temporary, and price increases over 2021 were unusually concentrated in particular areas, which does not indicate persistent inflation. The paragraph above suggests it is possible that new sources of inflationary pressure may arise if the pandemic largely ends, but these again are temporary, although temporary needn’t mean over in a few months.

Temporary inflation a bit above UK and European levels is a price well worth paying for output after the pandemic 4-5% higher than most other G7 countries, including the UK. The only reason not to try and emulate the US in enacting a strong fiscal stimulus is if you think temporary inflation becomes embedded in expectations i.e. real wage [1] increases in excess of productivity gains.

It would be a healthy sign if interest rates rise a little because Biden’s (now much more modest) infrastructure plan will maintain demand after all the pandemic effects are over (if they are ever over). The big danger for the Fed is if this doesn’t happen, they still raise rates because of temporary increases in inflation, and the economy dips in time for political gains for the (now anti-democratic) Republic party.

Just as current US inflation is unlikely to negate the achievement of having such a strong recovery from recession, relatively poor performances in most other G7 countries (UK included) are shown to be a policy choice, in most part because deficit concerns ruled out a large fiscal stimulus. Permanently losing a few percentage points of output to the pandemic is such a bigger cost than temporary inflation at 5% rather than 7%.

After 2010 everyone pivoted to austerity outside China, so it was difficult to find a country that showed its folly. It is a tribute to Biden and those around him that at least one country has now understood the folly of worrying about the government’s deficit in a recession. It is the example of the US that interviewers should mention the next time Conservative ministers trot out their line to take on the UK recovery.

[1] By real wages here I mean deflated by output prices, not consumer prices.