For macroeconomists

I finally got round to reading this paper by Iván Werning - Managing a Liquidity

Trap: Monetary and Fiscal Policy. It takes the canonical New Keynesian model,

puts it into continuous time, and looks at optimal monetary and fiscal policy

when there is a liquidity trap. (To be precise: a period where real interest

rates are above their natural level because nominal interest rates cannot be

negative). I would say it clarifies rather than overturns what we already know,

but I found some of the clarifications rather interesting. Here are just two.

1) Monetary policy alone. The optimum commitment

(Krugman/Eggertsson and Woodford) [1] policy of creating a boom after the

liquidity trap period might (or might not) generate a path for inflation where

inflation is always above target (taken as zero). Here is a picture from the

paper, where the output gap is on the vertical axis and inflation the

horizontal, and we plot the economy through time. The black dots are the

economy under optimal discretionary policy, and the blue under commitment, and

in both cases the economy ends up at the bliss point of a zero gap and zero

inflation.

In this experiment real interest rates are above their natural

level (i.e. the liquidity trap lasts) for T periods, and everything after this

shock is known. Under discretionary policy, both output and inflation are too

low for as long as the liquidity trap lasts. In this case output starts off 11%

below its natural level, and inflation about 5% below. The optimal commitment

policy creates a positive output gap after the liquidity trap period (after T).

Inflation in the NK Phillips curve is just the integral of future output gaps,

so inflation could be positive immediately after the shock: here it happens to

be zero. As we move forward in time some of the negative output gaps disappear

from the integral, and so inflation rises.

It makes sense, as Werning suggests, to focus on the output

gap. Think of the causality involved, which goes: real rates - output gap (with

forward integration) - inflation (with forward integration), which then feedback

on to real rates. Optimum policy must involve an initial negative output gap

for sure, followed by a positive output gap, but inflation need not necessarily

be negative at any point.

There are other consequences. Although the optimal commitment

policy involves creating a positive output gap in the future, which implies keeping

real interest rates below their natural level for a period after T, as

inflation is higher so could nominal rates be higher. As a result, at any point

in time the nominal rate on a sufficiently long term bond could also be higher

(page 16).

2) Adding fiscal policy. The paper considers adding government

spending as a fiscal instrument. It makes an interesting distinction between ‘opportunistic’

and ‘stimulus’ changes in government spending, but I do not think I need that

for what follows, so hopefully it will be for a later post. What I had not taken

on board is that the optimal path for government spending might involve a

prolonged period where government spending is lower (below its natural level).

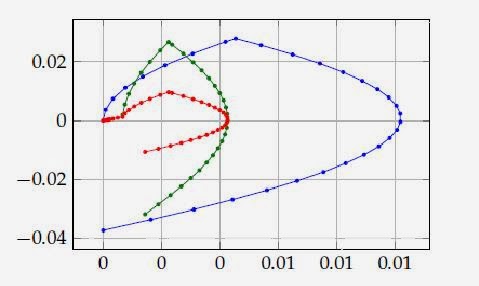

Here is another picture from the paper.

The blue line is the optimal commitment policy without any

fiscal action: the same pattern as in the previous figure. The red line is the

path for output and inflation with optimal government spending, and the green

line is the path for the consumption gap rather than the output gap in that

second case. The vertical difference between red and green is what is happening

to government spending.

The first point is that using fiscal policy leads to a distinct

improvement. We need much less excess inflation, and the output gap is always

smaller. The second is that although initially government spending is positive,

it becomes negative when the output gap is itself positive i.e. beyond T. Why

is this?

Our initial intuition might be that government spending should

just ‘plug the gap’ generated by the liquidity trap, giving us a zero output

gap throughout. Then there would be no need for an expansionary monetary policy

after the gap - fiscal policy could completely stabilise the economy during the

liquidity gap period. This will give us declining government spending, because

the gap itself declines. (Even if the real interest rate is too high by a

constant amount in the liquidity trap, consumption cumulates this forward.)

This intuition is not correct partly because using the

government spending instrument has costs: we move away from the optimal

allocation of public goods. So fiscal policy does not dominate (eliminate the

need for) the Krugman/ Eggertsson and Woodford monetary policy, and optimal

policy will involve a mixture of the two. That in turn means we will still get,

under an optimal commitment policy, a period after the liquidity trap when

there will be a positive consumption gap.

The benefit of the positive consumption gap after the liquidity

trap, and the associated lower real rate, is that it raises consumption in the

liquidity gap period compared to what it might otherwise have been. The cost is

higher inflation in the post liquidity trap period. But inflation depends on

the output gap, not just the consumption gap. So we can improve the trade-off

by lowering government spending in the post liquidity trap period.

Two final points on what the paper reaffirms. First, even with

the most optimistic (commitment) monetary policy, fiscal policy has an

important role in a liquidity trap. Those who still believe that monetary

activism is all you need in a liquidity trap must be using a different

framework. Second, the gains to trying to implement something like the

commitment policy are large. Yet everywhere monetary policy seems to be trying

to follow the discretionary rather than commitment policy: there is no discussion

of allowing the output gap to become positive once the liquidity trap is over,

and rules that might mimic

the commitment policy are off the table. [2] I wonder if macroeconomists in 20

years time will look back on this period with the same bewilderment that we now

look back on monetary policy in the early 1930s or 1970s?

[1] Krugman, Paul. 1998. “It’s Baaack!

Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap.” BPEA, 2:1998, 137–87. Gauti B. Eggertsson & Michael

Woodford, 2003. "The Zero Bound on

Interest Rates and Optimal Monetary Policy,"Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Economic Studies

Program, The Brookings Institution, vol. 34(1), pages 139-235.

[2] Allowing inflation to rise a little bit above target while

the output gap is still negative is quite consistent with following a

discretionary policy. I think some people believe that monetary policy in the

US might be secretly intending to follow the Krugman/Eggertsson and Woodford strategy, but as

the whole point about this strategy is to influence expectations, keeping it

secret would be worse than pointless.

Good post. Thanks for doing ones like this.

ReplyDelete"What I had not taken on board is that the optimal path for government spending might involve a prolonged period where government spending is lower (below its natural level)."

That's what I've been trying to say!

In a NK model, it is not a *high level* of G that increases the natural rate; it is a *low growth rate* of G.

Ideally, if G is initially at the microeconomic optimal level G*, and at time t0 you suddenly hit a liquidity trap that lasts T periods, you jump G above G*, then make G steadily decline to below G* at t0+T, then start increasing G again towards G*.

But if G can't jump (because there are no shovel-ready projects and it takes time to change G), the third best fiscal policy is to make Gdot negative for T periods. Which is very different from Old Keynesian fiscal policy.

"Here is a picture from the paper, where the output gap is on the vertical axis and inflation the horizontal..."

It is murder on my neck when people draw Phillips Curves with the axes the wrong way round!

The assumption that government spending is less efficient than private spending is probably a bad assumption. Whether or not this is the case comes down to what sorts of projects money can be spent on. Surely infrastructure spending, aid to states so they can restore normal levels of spending, and investments in renewable energy sources are actually more efficient than what the private sector would do, for the reason that the private sector would not do those things (or, at least, not to the same degree), but they are nevertheless beneficial to society (and the economy). I'm sure there are situations where we have a government that is currently pursuing an optimal budget where it is doing all of the tasks that are economically most efficient for it to do, and in that situation stimulus will necessarily be a reduction in efficiency.

ReplyDeleteBut I don't think we're anywhere close to that situation in the US, at the very least. And probably not in the UK either after a number of years of austerity. Public spending is far too low, and there are huge numbers of possible programs to spend money on that would increase rather than decrease economic efficiency of said spending.

This seems to support the conclusion that combining monetary and fiscal policies (in the extreme, through helicopter drops) is the most effective way to escape the liquidity trap (see http://www.voxeu.org/article/unconventional-monetary-policies-revisited-part-ii), a point made since the very old days by such eminent and diverse economists as Henry Simon, Irving Fisher, John Maynard Keynes, Abba Lerner, and Milton Friedman, resurrected by Bernanke in the early 2000s, and recently re-articulated by McCullay and Pozsar, Turner, Wood and the Neo-chartalists or MMTers.

ReplyDeleteOne quick comment on Jason Dick's, with which I fully agree when the issue is one efficiency. Yet, when it comes to trying to move the economy out of prolonged depression or outright deflation, effectiveness might have priority over efficiency, and trasfering public money or reducing taxes to (credit constrained) households and firms can be more rapidly engineered than spending on infrastructures, which typically requires long gestation periods before the money can be actually spent.

It's not just a phobia of trying fiscal policy, it's even a failure to believe your lying eyes when it's happening.

ReplyDeleteThe BBC 'Japan moves close to beating 15 years of falling prices' 27 December 2013 has it that:

"Japan is now more than half-way towards meeting the central bank's goal of achieving 2% inflation by about 2015. This has been due to a massive monetary stimulus policy aimed at weakening the currency and spurring more spending."

Whereas Stiglitz article 'The Promise of Abenomics' and Krugman and Eichengreen all have it as the catchy "three arrows" policy in which one of the arrows is fiscal stimulus.

I've been watching the BBC on Japan since the right-wing Abe started his (weaponised) Keynesianism.

The BBC has editorially banned the term 'fiscal stimulus' and I want to know who is responsible.

I'm happy you finally got around to reading Werning's paper. Now maybe you should read John Cochrane's paper recent paper on the zero lower bound/ New Keyenesian liquidity trap theory. Even if you don't agree with his conclusions, you should at least be aware of the possibility of multiple equilibria here and the difficulties this poses for deciding what to do in the real world (since it's as if we live in a regime switching world without knowing clearly in which regime we are in, and good government policy depends a lot on which regime you're in).

ReplyDeleteI addressed the issue of equilibrium selection in this post: http://mainlymacro.blogspot.co.uk/2013/08/expectations-driven-liquidity-traps.html

Deletewhich you commented on. There I argue that the indeterminate equilibrium is not a plausible one for the UK or US. Tell me why you disagree.

The choice of equilibrium of Werning(2012) still have weird properties as shown by Cochrane, for example the output gab is larger when the prices are less sticky. So I don't see that the right equilibrium is chosen by Werning.

DeleteAnon: As we do not observe worlds where prices are sticky and worlds where they are not, how can we say something is weird. We should choose an equilibrium concept that makes sense given the information people have, and that is what Werning, Woodford and others do. I have yet to read any good justification that the indeterminate equilibrium makes sense in a world with clear inflation targets. If you know of one, please let me know.

DeleteI am not sure I understand it completely. It still seems to me that the equilibrium that Werning(2012) has chosen leads to some weird/counter intuitive results, such as large multipliers to wasted government spending and these increase when price become less rigid. These results are according to Cochrane a direct result of the choice of equilibrium. Anyway what do you think of the alternative equilibrium suggestion by Cochrane. The local-to-frictionless equilibrium in which the economy approaches the steady state as t goes backwards in time.

DeleteMy discussion of why Werning's equilibrium is the right one to choose in an economy with a clear inflation target is in the post that I reference at the start of this thread - please read and then comment. But I'm curious - why do you call it "wasted government spending"?

DeleteI am referring to Cochrane's paper The New-Keynesian Liquidity Trap, (I thought that was what daniels was referring to, and what we were talking about) http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/john.cochrane/research/papers/zero_bound_2.pdf, not the one about the Determinacy and Identification with Taylor Rules. Maybe that is why we are talking past each other. Anyway Cochrane add a shifter variable to the Phillips curve which represents wasted government spending, and find that because it creates inflation then it has a large positive multiplier and it increases when price become less rigid. I hope this had cleared things up.

DeleteIn Werning's paper G is not wasteful - hence the confusion. Let's stick to the Cochrane paper to avoid this. As Cochrane says, the choice of equilibrium is the Feds, and I think the conventional choice is both what the Fed will do and what people expect them to do. So its the right choice for analysis.

DeleteCochrane says that this is odd, because paths before T are explosive backwards. I do not find it odd. Think about UIP, where you impose interest rates to be above world rates for T periods. The exchange rate appreciates and then converges. All that is happening here is that you add feedback from inflation to the output gap. I also do not find the price flexibility result odd either, using the same logic. However take Cochrane's alternative local to frictionless path. That has inflation jumping up to 5% as the ZLB constraint hits, and the output gap is positive while the constraint holds. That is weird, as there is no recession!

Thanks for the answers, these help me understand it better. Still struggling with understand the implication of price flexibility, but I guess I just have to think a bit harder.

ReplyDelete