It’s the second leg of a cup tie. Your team you support lost badly in the first leg, but in this match their opponents made a series of huge defensive errors, resulting in a number of goals for your side. Your team has turned the tables, and are two up on aggregate. With thirty minutes to go, what tactics should they adopt? Should they continue to attack, hoping for more errors from their opponents or a moment of attacking brilliance? Or should they close the game down, removing any chance of their opponents scoring a goal that could open the tie up again?

Well before Starmer announced that he would not pledge to end the two child limit for Universal Credit it was clear Labour were trying to close the game down by avoiding any commitments to spend more than the government beyond those few already made. The Conservatives and their press will run with ‘Labour’s tax bombshell’ whatever Labour do, but if those claims lack any credibility in the broadcast media they will have limited traction. As Labour ends up trying to hold the ball by their opponent's corner flag, the disappointment of those watching is clear, but fans know above all else they want their side to win. [1]

I have no idea whether this is a good or bad political tactic in terms of winning the next election. The experience of 2019 shows the dangers of a campaign with a lot of spending commitments, but the success of the 2017 campaign suggests a few well chosen spending increases can attract otherwise apathetic voters. However, in defending Labour’s current tactic it is never a good idea to parrot falsehoods, even if you are only ‘coining a phrase’.

What should be clear to anyone looking at the current state of the public services is that the government’s current spending plans are just not credible, and so the next government will have to increase day to day public spending. Unless the economy is in recession or there is a significant risk this may happen, that extra current spending needs to be matched by additional taxes. (This is not the case for public investment, which should be matched by additional borrowing rather than higher taxes.)

The reason why current public spending has to increase compared to current plans can be demonstrated in two ways. The first is just to note each area where public services are failing badly through lack of funding, rather than lack of ‘reform’ (whatever that is). The second is to look at international comparisons. As the former is much more common than the latter, I will look at international comparisons here, drawing on some earlier analysis.

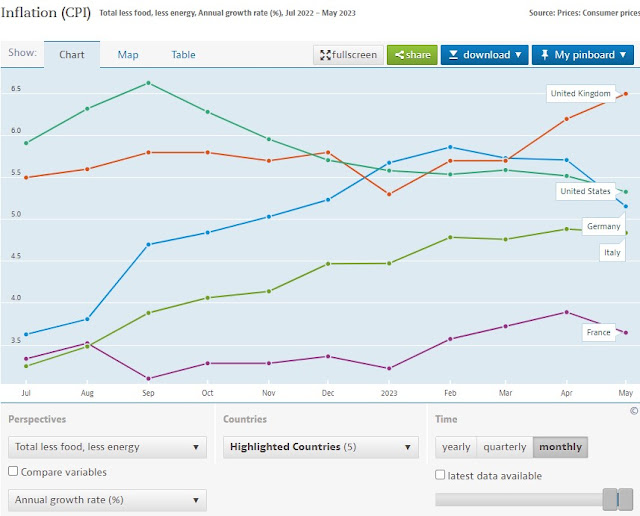

But before doing this, it is worth repeating that a third, frequently used way is largely meaningless. This is to look at historical trends in UK taxes and public spending as a share of GDP, and note that both are at historic highs. It is a meaningless because the share of health spending as a percentage of GDP has been rising in nearly every country over the last few decades, so the tax to GDP ratio will have to rise with it in any country where health services are publicly funded.

International comparisons based on public spending or tax levels are useful, but they too can be misleading because they take no account of the division of tasks between the state and the private sector in different countries. In the United States, for example, much more health provision comes from the private sector than in most European countries. In France the public sector provides more of the pensions people receive than in the UK. A much better way of doing international comparisons is to add up all spending on certain categories, whether that spending is funded through taxation or through the private sector, and look at their share in total GDP.

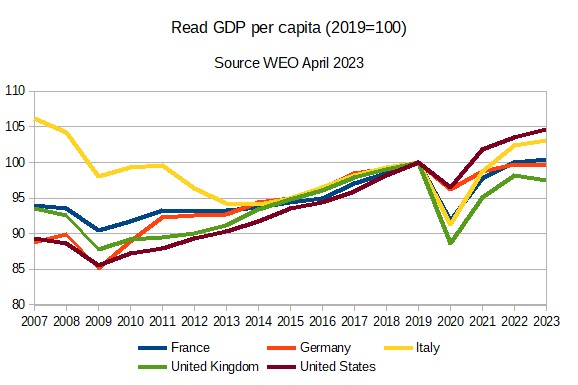

The OECD does this for what they call ‘social spending’, which is essentially welfare spending (including pensions) and health spending, but excludes education and some other areas of public spending. Of the G7 countries, in 2019 the UK had the lowest share of social spending in GDP. (2019 is the latest data we have, but when we get it data for 2020-2 will be heavily distorted by the pandemic.) The two countries with far higher share of social spending than the UK were not in Scandinavia but France and the United States. This shows how international comparisons of public spending and tax can be misleading. The US in 2020 was the only country with a lower tax rate than the UK because it doesn’t have an NHS, but social spending as a share of GDP is much higher. There is nothing inevitable about the UK having the lowest welfare and health spending share among the G7: in 2010 we were ranked third, not last. Labour should aim to completely reverse that 14 year decline.

These international comparisons show there is plenty of scope to raise public spending and taxes. So the only question for the next Labour government is when this happens. Does it follow what happened in 1997 and stick to Conservative tax and spending plans until they become intolerable towards the middle of their first five years, or does Rachel Reeves raise taxes and spending in her first budget?

1997 is an obvious template, and Reeves may well want to follow in the footsteps of our most successful and influential Chancellor in living memory. [2] Labour are rightly committed to substantial green investment (albeit phased in over a few years), and she may feel that delivering this without frightening the markets is a necessary precondition to getting the growth that will bring in higher taxes that will allow higher spending. This suggests following Brown in sticking to Tory spending plans over the first two years, and hoping that some combination of higher growth and enhanced credibility will allow higher public spending nearer the election.

However, as I have noted before, 1997 was different to the situation Labour will find itself in as a new government sometime during 2024. Public service provision was poor then, but it is at critical levels today, and in the NHS at least poor public provision is hurting the economy In addition, relative public sector pay has been cut substantially, and that is unsustainable. The fiscal plans that Hunt has given the OBR, which imply further austerity, cannot be delivered by any government. A Labour government that tried would tear itself apart.

The danger in trying to stick closely to Conservative spending plans, even for two or three years, is that inaction on public service provision and pay will mix public disappointment with damaging internal wrangling. When taxes and spending do eventually increase, Reeves will be seen as having been forced to do this by her party, rather than being in control. In addition it may be too late to see the benefits of higher spending before the next election. It is not impossible that, to protect Starmer’s own position, Reeves could lose her job.

There is therefore a strong case for Rachel Reeves to raise spending and taxes in her first budget. Even Gordon Brown introduced a windfall tax in 1997! It will take time for the benefits of higher public spending to be seen in lower waiting times and better staff retention, so the sooner Labour starts the better. There are also strong political arguments for starting boldly rather than gradually.

There are some obvious tax increases that can be made that will impact mainly on the well off, like a higher top rate, aligning capital gains taxes with income taxes, and windfall taxes on Banks while interest rates remain high. But I think there is a strong political argument for going beyond these, and to raise taxes that are paid by much larger numbers of people. An obvious candidate from a political point of view is to implement the increase in national insurance contribution rates (along with some adjustment in who pays) that Sunak initially proposed, then Truss reversed but Hunt did not reinstate.

How does Labour do that without seeming to contradict everything they are saying now? Once upon a time oppositions once elected could claim the ‘books’ were in a much worse state than they had imagined, but that is less credible now we have the OBR. Equally it is hard for Labour to claim that the public services are in a worse state than they had thought when you just need to look at published data to see how bad things are. (If you prefer first hand accounts, read this.) But whatever excuses they use, the need for them is another reason why making them once at the beginning of their term, rather than as a steady stream throughout it, makes political sense.

From both an economic and political point of view, announcing large tax and public spending increases in the first Labour budget makes a lot of sense, and is preferable to any alternative. We can only hope that Labour can switch quickly from focusing on winning power to being an effective government once they return to power.

[1] This also means that if the government pledges to reduce or even eliminate inheritance tax, Labour will probably match that pledge, as inheritance tax is an unpopular tax (because most people do notunderstand how few pay it). But, as this post makes clear, there is zero chance that Labour once in power would reduce inheritance tax.

[2] In retrospect Brown’s first budgets were way too tough, with public sector net debt falling from 37% to under 30% in just three years. A lot of that was due to unexpectedly high tax receipts, but public spending also fell as a share of GDP. There is no evidence that any of this was necessary to win some kind of iron Chancellor credibility test.