Before answering this question, we need to define what the OECD counts as social expenditure. It is mainly a combination of what we call welfare spending (including pensions) and health spending, but it also includes incapacity-related benefits, active labour market programmes, as well as unemployment and housing benefits. What it is not is just public social spending. In all OECD countries individuals spend some of their own money (either directly or through their employer) on social expenditure. In the UK, for example, private social expenditure exceeded 6% of GDP in 2019 according to the OECD, mainly in the form of pension contributions.

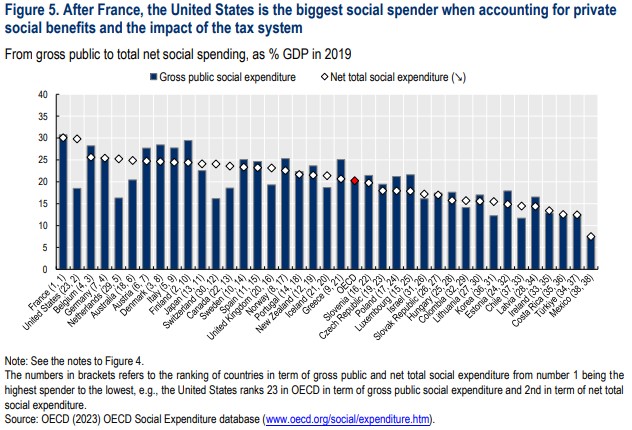

The answer to the question posed by the title, using this data, comes from the diamonds in the chart below.

That France is top is probably not a huge surprise , but that the United States is second (just below France) might. The blue columns represent public (state) social spending, and the US is indeed fairly low here, but the US has the second highest private sector social spending among OECD countries. France is at the top partly because it has a very generous pension system (see this recent post), while the US is so high in part because it has a very expensive (and inefficient) health system.

Given how many hits of the keyboard are spent discussing public spending on health, pensions and other items, combining public and private spending in this way can be a useful corrective. What matters to most people is how big their pension is, or the quality and accessibility healthcare is, rather than the form in which they pay for it.

The OECD splits private social expenditure into two types: mandatory and voluntary.

In countries where private social spending is high, in both Switzerland and Iceland it is largely mandatory, in Canada and the UK it is almost all voluntary, while the Netherlands and the US it is mixed. The last two involve mandatory health payments (Obamacare in the US). Mandatory payments might give consumers some choice over providers, but otherwise mandatory payments are similar to a tax. In the UK the largest component of voluntary social expenditure involves private pensions. Again this gives consumers more choice than any state pension would, but for individuals the option of not buying is hardly advisable, which means they do not have additional money to spend on other things. The big advantage of a state pension over private pensions is that the latter exposes individuals to interest rate risk at the time their pensions need to be turned into an annuity.

So while the choice between public, mandatory private and voluntary private provision is important, the amount of social expenditure from whatever source is at least as important. Of the G7 countries, which spent the least on social expenditure in 2019? In the chart above it is the UK. This has not always been the case, as the following chart shows [1].

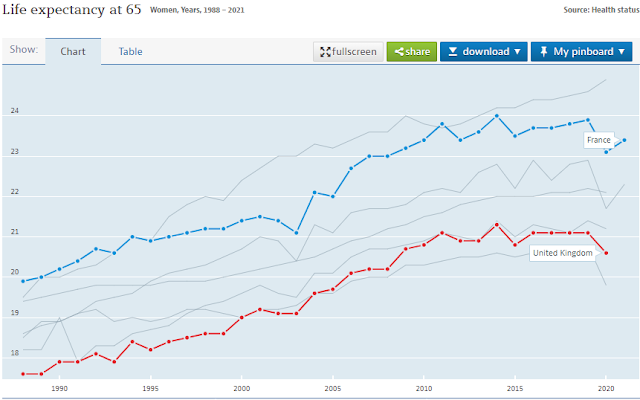

In 2010 the UK had the third highest social spending in the G7, but the trend over the following decade has been consistently downwards. Because our Conservative government has been obsessed with cutting taxes and squeezing the state, without much attempt at reducing the scope of what the state provides in the UK, we end up having less spent in many areas (including social expenditure) than most people want. [2]

This is a crucial fact to bear in mind the next time someone moans about how much the state spends on health, pensions or some other item of welfare spending. It is a point I try to emphasise whenever I discuss public spending on health or pensions, or aggregate public spending figures. An emphasis on total social spending is also crucial when looking at data on tax.

According to OECD figures for 2020 for the G7, the country with the highest total tax as a share of GDP is France at 45%, followed by Italy at 43%. Germany is significantly lower at 38%, and then Canada and Japan lower still at 34% and 33% respectively. The UK is at 32%, while the US is lowest at 26%. The UK is a low tax country, with only the US lower among the G7. But as the figures above show, these differences reflect the form of financing of social spending at least as much as the total amount of social spending. Those who suggest that low taxes in the US mean that people there have more money to spend are being disingenuous, because US citizens need to pay, either directly or indirectly, for social goods that are provided free in other countries.

For this reason much of the public debate about the size of the state misses key issues. What should be central to this debate is how types of spending, including social spending, are financed rather than the amount that is spent. For example, is it better for the state to provide most pensions (as in France) or is it better for individuals to pay for their own pension schemes? Is a health service privately funded via insurance companies (either voluntarily or through mandated payments) less efficient than something like the NHS. How much tax people pay will follow from that discussion, yet tax is all too often how such discussions start.

[1] Data for 2019 in four of the G7 countries are not shown here, perhaps because data in the previous chart is partially estimated.

[2] Those who can afford it can try and make up the difference by, for example, buying private medical insurance, but the quality of private sector health care in terms of medical outcomes is highly dependent on the NHS.