I think most people understand that the inflation we are seeing at the moment across the developed world has very little if any to do with excess demand (the famous too much money chasing too few goods) but is about external shocks to the price of commodities, and supply problems that emerged because of the pandemic and the recovery from it. In addition both types of inflationary shock are likely to be temporary: commodity prices are unlikely to continue to rise and most supply problems caused by the pandemic will be resolved.

If this is the case, why do central banks need to raise interest rates, particularly as higher commodity prices will reduce real incomes which is deflationary? Given the normal lags in monetary policy, higher rates will have little impact on current inflation, so why reduce demand and inflation in the future when inflation has largely disappeared? The answer is fear of a wage-price spiral. If wages rise to some extent as a result of price inflation, this will raise costs which will raise future prices. The received wisdom in central banks (from the mid-2000s as well as the 1970s) is that some reduction in demand is required to stop a wage-price spiral developing.

The likely level of excess or insufficient demand in 2022 should be crucial in this respect. If there is already insufficient demand, and lower real incomes will only make that worse, then central banks have little or nothing to do. In contrast if the labour market is currently tight and likely to stay tight the dangers of a wage-price spiral are much higher. It therefore makes sense to start any assessment by looking at output levels.

In terms of the major economies, we did get a V shaped recovery from the pandemic, but where the V stands for vaccines. As soon as vaccines became widely available, the economy expanded rapidly, as I showed here. Vaccines removed the need to lockdown the economy, and gradually gave consumers confidence to engage in areas of social consumption.

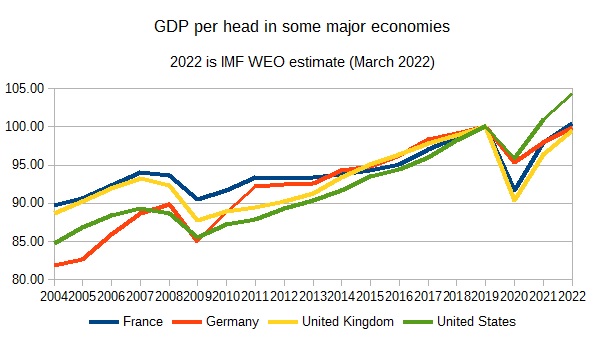

However the recovery was not equally strong in the major economies. Here is an updated chart of one I showed in that earlier post, looking at GDP per capita (2019=100) rather than GDP.

The US not only had a less severe COVID recession than the UK and France, but it has also had a much stronger recovery than the other three economies. (You can also see how the last ten years have been a decade of relative decline for the UK, matched only by France because of Eurozone austerity around 2013.)

Matching this is a clear hierarchy in inflation rates. If we look at Core inflation in each country, the US is the highest at 6.5% for March, while Germany is at 3.4% for the same month and France 2.5%. However UK core inflation is surprisingly high, at 5.7%, even though it has had a similar recovery to France and Germany. One of the reasons is Brexit, which we discuss below.

It is of course possible that the pandemic has caused a permanent reduction in the supply of goods, either through lower technical progress, capital or labour. I find it difficult to believe that the pandemic has had a permanent impact on technical progress, or that lower investment during the pandemic cannot be rectified by high investment later as part of a sustained recovery. The experience of the UK and elsewhere before the GFC was that recessions did not lead to a permanent reduction in productive potential.

The pandemic does seem to have had, so far at least, a negative impact on labour supply in the UK and US among older workers, in what has been called the Great Retirement. There are lots of possible reasons for this, including less need to work for some as a result of additional savings over the pandemic. However another potential explanation is Covid itself, and in particular Long Covid, as this Brookings study outlines, or the indirect effect of Covid because other health problems have not been fixed as quickly as they should. (For the equivalent for the UK, this briefing note is a good place to start.) France has avoided similar problems, in part because of early retirement.

This might suggest that US growth since 2019 may have exceeded the growth in supply, but elsewhere it is completely implausible to suggest these problems are big enough to give you zero growth in potential since 2019. This suggests the following:

-

In the US, relatively high inflation and strong growth combined with a reduction in labour supply could indicate an economy above its ‘constant inflation’ position (i.e. has excess demand).

-

France and Germany, with weaker inflation and projected output per capita in 2022 at around 2019, indicate economies probably below their constant inflation position, suggesting excess supply in these economies.

-

In the UK we have a special case due to Brexit.

Here are a few thoughts on each in turn.

United States

With high vacancies and wage growth at around 5% in 2022Q1, high inflation in the US has become more broadly based than it once was. An important reason for this, which is shared by the UK, is a drop in labour supply after the pandemic. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta has hourly or weekly earnings at 6% in March.

The IMF’s projected growth for 2022 implies annual increases in underlying output since 2019 of around 1,4%, which does not at first sight seem unreasonable. However if the pandemic has reduced the supply of labour or some other element of potential in a significant way, this growth would indicate excess demand. This is the IMF’s view, which suggests excess output of over 1.5% in 2022. This judgement seems to be shared by the Federal Reserve, which recently increased interest rates by 0.5% on top of an earlier 0.25% increase. However, there are two major risks in the monetary tightening which is currently underway.

The first is that this contraction in labour supply may be temporary. The second is that the economy is heading for a significant downturn or even recession of its own accord, without the help of policy. As higher prices squeeze real wages, consumption growth may decline significantly which will drag down GDP. (The fall in GDP in the first quarter of 2022 may be erratic, or it may indicate this is already happening.) If either happens, raising interest rates rapidly could turn self-correction into a period of serious insufficient demand.

If neither risk occurs, I think it is wrong to conclude that Biden’s fiscal stimulus was ill-judged, for three reasons. The first is that very little of current high headline inflation would have been avoided if that stimulus had not occurred. The second is that a long period where interest rates are close to their lower bound indicates an inappropriate monetary/fiscal mix, and some correction such that a fiscal stimulus leads to moderately higher interest rates will allow monetary policy to more effectively respond to any future downturns. [1] Third, that stimulus was probably the only politically feasible way to reduce poverty quickly.

France and Germany

Whereas the IMF expects the US to have excess demand, it projects both France and Germany to have insufficient demand in 2022. It would be quite wrong, therefore, to argue that ECB interest rates should rise. Indeed, with interest rates at their lower bound, and higher energy and other prices likely to cut personal incomes, there is a strong case for a significant fiscal stimulus to raise GDP.

United Kingdom

Is the UK more like the US (current excess demand) or France/Germany (current deficient demand)? The level of core inflation, and the actions of the Bank of England in raising rates, suggest the UK is more like the US. Both also have tight labour markets and nominal wage inflation that is inconsistent with a 2% target. But I would argue that is where the similarities end.

The first obvious point is that projected growth in output per head in the UK has been much weaker from 2019 to 2022 than in the US. As I have already noted, the UK looks much more like France and Germany in this respect. A major reason for that is fiscal policy. Instead of sending a cheque to every person (as in the US), the Chancellor has announced a freezing of tax thresholds and higher NICs. [2]

So why is UK core inflation nearly as high as the US, and much higher than in France and Germany? One important reason is Brexit, which has raised UK inflation through various routes. We already know that the immediate sterling depreciation after the referendum result increased inflation in earlier years. In addition this study estimated that the Brexit trade agreement has directly increased UK food prices by 6%. This is because additional barriers at the border (checks, waiting times, paperwork) are costly. Importers can switch to non-EU sources, but that will also mean higher prices. More generally the Brexit trade barriers may lead to the creation of new, but less efficient, supply chains, pushing up prices. Finally these trade barriers mean reduced competition, allowing domestic producers to increase markups.

One additional possible inflationary consequence of Brexit that has been talked about a lot is due to labour shortages in low paid jobs because of the ending of free movement. While those shortages are real enough (vacancies for low paid jobs have grown much more rapidly), up to the end of 2021 this does not seem to have led to higher pay growth according to this IFS study (see chart 3.2 in particular). As a separate briefing note from the IFS points out, there is one sector that has shown rapid earnings growth recently: finance. (For a good discussion of the UK labour market, see here.) If we look at earnings growth in the first two months of this year, however, we see quite rapid growth in earnings in the wholesale, retail, hotels and restaurants sector. [3]

Yet all these inflationary impulses due to Brexit are temporary, reflecting the one-off nature of the trade barriers, reduced competition, labour shortages etc. While the increase in wages in the US is broadly based, that is not the case in the UK, suggesting a relative wage effect rather than general inflationary pressure. As a result, I think there is a serious danger that the MPC are seeing misleading parallels between the UK and US, whereas in reality the UK’s situation is much more like France and Germany with a short term Brexit inflationary twist. If I am right, then monetary tightening coupled with fiscal tightening and higher prices for energy and food could spell recession. [4]

My view on likely interest rate moves is not shared by the markets, which are expecting many more rate increases from the MPC. The Bank’s arcane practice of using these market expectations in their main forecast has confused a lot of people. If you want an idea of what the majority of the MPC currently think will happen, it is better to look at their forecast using current interest rates. That shows inflation falling to just over 2% by mid-2025, and annual GDP growth of between zero and just over 1% in every quarter of 2023, 2024 and 2025H1. That is not exactly an exciting prospect, but it is not a serious recession either. The problem, as I noted here, is that forecasts are poor at predicting recessions.

The MPC may be right or wrong, but the outcome in either case is pretty dire for the UK economy. If they are right to raise rates, then the best the UK can do after the pandemic is return GDP per capita to 2019 levels. That will mean that the pandemic in the UK, and the policy reaction to it, has lost at least three years worth of growth. If the MPC is wrong, raising rates will cut short a recovery in output and risk a recession which once again [5] risks policy induced deficient demand choking off long run supply, making everyone in the UK permanently poorer.

[1] Some might argue that in an ideal world fiscal policy should always respond to excess demand or supply, and therefore interest rates can stay very low. However the US is perhaps the country which has a political system where this kind of fiscal activism is least likely to occur without prior fundamental reform.

[2] In judging the impact of any fiscal stimulus, looking at measures of cyclically adjusted (or ‘structural’ or ‘underlying’) budget deficits can be very misleading. To take a clear example, if a country announces a five year programme of buying fighter planes from another country, its deficit increases but this provides zero stimulus to the domestic economy. The Biden stimulus was like helicopter money, except the rich got nothing. Furlough on the other hand gave people money in proportion to their salary. A stylised fact is that the wealthier people are, the less of any government transfer they will spend, and the more they will save. As a result, giving a fixed amount to the non-wealthy is much more effective at boosting demand than a furlough type scheme.

[3] The Bank of England say “underlying wage growth is projected to pick up further in the next few months”, so perhaps they are expecting a delayed reaction to high vacancies.

[4] It is easy to blame the MPC, but these issues are complex and its remit limits how much the MPC can ignore a sharp rise in inflation. I certainly do not think governments are better placed to make these economic judgements. What I think can be done is change the MPC’s remit to place more emphasis on output while making the inflation target more long term, as I suggested here.

[5] I say again because that has to be part of the story that explains the lack of recovery after the Global Financial Crisis, although the blame then lies with fiscal policy (austerity).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Unfortunately because of spam with embedded links (which then flag up warnings about the whole site on some browsers), I have to personally moderate all comments. As a result, your comment may not appear for some time. In addition, I cannot publish comments with links to websites because it takes too much time to check whether these sites are legitimate.