This was not quite the Autumn Statement many people were expecting. Public spending on health and schools was increased a bit in the short term, welfare payments were indexed to inflation with some icing on top, and cuts to public spending were postponed to after the next election so may never happen. If we discount the latter, the fiscal tightening was all about raising taxes by not indexing allowances. By 2023/4, the ratio of taxes to GDP (national accounts definition) will be nearly 37'5%, compared to just over 33% in 2019/20.

Of course none of that means that most public services are not still in crisis, or that the government’s assumptions about public sector pay are any less painful (and strike creating), or that higher food and energy prices are not going to stretch many people’s budgets beyond their limits. The OBR’s forecast for falling average real disposable income last March was terrible (the worst since WWII), but their forecast yesterday (with less energy subsidy from the government) was a lot worse.

The coming recession

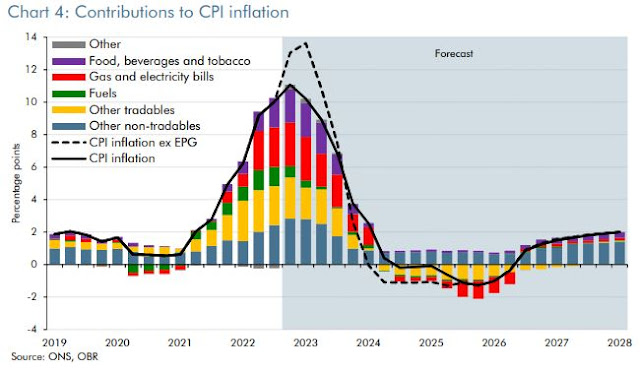

The OBR has predictably followed the Bank in forecasting a recession, which we have already started. What is most eye-catching about their short term forecast is what they expect to happen to inflation. The chart below looks complicated but focus on the black line, which is their forecast for inflation.

The OBR expects inflation is currently near its peak, but it will soon come crashing down. Indeed during 2024 it will fall to zero, and be negative during 2025/6, helped by modest falls in energy and food prices.

If you think that is implausible, here is the reason (bottom left quadrant).

The OBR are following their normal practice of taking their forecast of interest rates from market expectations. These expectations have Bank rate rising to 5% early next year, and then falling back to about 3.5% by 2028. There is no way this will happen if inflation follows the path the OBR are predicting. As the Bank themselves say they don’t believe these market expectations about what they will do, it is slightly surprising that the OBR have stayed with them. It makes the OBR’s forecast a bit weird, but I will try and rescue what I can in the comments below.

The OBR’s forecast for GDP is similar to the Bank’s latest forecast until about the middle of next year (their Chart 14), with both predicting falling GDP. Thereafter the OBR is much more optimistic, forecasting a recovery in output of 1.3% GDP growth in 2024 compared to a predicted further fall of 0.9% by the Bank. But the OBR are much more pessimistic about the path of GDP than they were in March (see Chart 1), which in the short term is because in March they were not forecasting a recession, and in the medium term because they now think energy prices will be permanently higher which will reduce potential GDP. This is one of the reasons for the need for fiscal consolidation in the Autumn Statement.

Another is higher debt interest payments caused by higher interest rates and higher debt. But here the implausibility of the path for short term rates assumed by the OBR matters. These rates will undoubtedly be lower, which will reduce borrowing costs particularly into the medium term. So some if not all of the cuts to government spending pencilled in for later years might not be necessary even if Sunak remains PM by then (see Table 3 and page 51).

Of course with cuts to personal income like those forecast, higher interest rates and rising taxes (excluding energy subsidies), the recession could easily be deeper than the OBR or Bank are forecasting. Is the OBR’s forecast for the recovery plausible? Well lower interest rates than they are assuming would help, but much depends on consumers. The OBR have the savings ratio falling to just under 5% next year and 2024, but then only recovering slightly to just over 5% thereafter. That is below the historic average, but may be reasonable given how much consumers saved during the pandemic.

The fiscal stance

The Chancellor has sensibly avoided calls from some of his MPs and others to cut spending in the short term, as such cuts would not have been credible. His income tax increases over the next few years will not help ease the coming recession and subsequent recovery, but their demand impact will be smaller than spending cuts, and they are probably necessary in the longer term. His failure to allow more for public sector pay will cause considerable disruption in the short term.

The government likes to say it is fiscally responsible. But one definition of fiscal responsibility is sticking to your own fiscal rules. It’s worth remembering that in 1998 Labour set out fiscal rules which guided policy for 10 years until the Global Financial Crisis. In contrast, since 2010 I have lost count of the number of times the government has broken and then changed its own fiscal rules, and today added to that count as we regress from a current deficit to a total deficit target so public investment could be cut a little (it falls from 2024 onwards).

So in the short term this Autumn Statement does very little to end the crisis in most public services, and we will have public sector strikes to look forward to. It also does nothing to moderate the forthcoming recession or help the subsequent recovery, although responsibility for the former has to be shared with the Bank. In the medium term, more sensible fiscal rules (see here) plus likely changes in the forecast will reduce or eliminate the need for public spending cuts after the election.

In political terms this Autumn Statement does nothing to enhance the Conservatives chances at the next election. Far from setting traps for Labour, promising spending cuts after the election is not a winning strategy when public services are already on their knees. If the OBR is right, and 2024 does bring a recovery in output along with falling inflation and interest rates, it gives the government something to talk about, but with real personal disposable income having fallen by 3% in each of the previous two years then voters’ memories will have to be very short to celebrate this.

One final point. The Chancellor presented a plan with far higher debt and deficits than previously, and with public spending cuts in the medium term that almost certainly will not happen. The markets didn't care. All those who implied that the markets are just waiting to punish any Chancellor that presented medium term plans that were not credible and tough have been proved wrong, just as they were wrong in 2010. What Kwarteng did was cause major short term uncertainty about the path of interest rates, which is why the markets reacted to his fiscal event. Yesterdays Autumn statement, and the lack of reaction to it, show once again that the markets are not some kind of policeman enforcing fiscal orthodoxy.

The Western economies are undergoing a congruent stress caused by 12 years of antecedent QE, generating record-level consumer inflation and followed by even a more historical 11 month rate of accelerated central bank QT. UK's consumer inflation problem, as pointed out, hasn't quite peaked.

ReplyDeleteSir Isaac Newton, as brilliant as he was, did not do financially well in the South Sea bubble. Elon Musk, certainly no Issac Newton, is likewise not doing well in the current US and global bubble, which is, arguably, qualitatively worse than 1720.

And Tulip history repeats itself with an interval of 385 years.

Dutch Tulips 1636-37 and crypto Tulips in USD 2022.

Wouldn't it be a thing if the asset-debt macroeconomy was ordered on a scale equivalent to Newton's invented calculus to describe planetary motion.

Hmm...