See also postscript below written shortly after the Budget

To say that much of the media treats Budgets as if the government was a household is not really accurate. Much Budget analysis treats the government as a cash constrained household, such that any change in expected tax revenue is regarded as money the Chancellor has to spend or give away. Most households don’t work like that, because they have the capacity to save and borrow. The government of course finds it much easier to borrow than households.

Unfortunately some governments encourage the media’s attitude to Budgets. On this occasion, however, the government’s fiscal rules are medium term, with targets always five years into the future. So there is nothing in these fiscal rules to suggest that temporary improvements to the government’s fiscal position need to be spent or given away. The reason they are likely to be spent or given away in the forthcoming budget is because we are close to an election. But because many in the media treat the government like a cash constrained household, what in reality is fiscal electioneering will be portrayed as normal practice.

The forthcoming election is likely to influence Chancellor Hunt’s first Budget in two ways. First, he will want to produce fiscal giveaways that will make newspaper front page headlines the next day, and perhaps sway some voters to vote Conservative. Second, he will want to try and get the economy growing again as quickly as possible. The reason why can be seen from this chart.

Whereas the US economy at the end of last year had GDP per head around 4% above its level at the end of 2019, the UK economy had GDP per head around 2% lower. This number may be flattering to the US because at the end of last year at least it was probably running a little hot, but the same is true of the UK yet GDP per head is still significantly lower than before the pandemic. The UK’s relative performance over the last three years has been even worse than its performance in the decade since 2010. The Chancellor will be desperate to see some positive economic news before the election, and hope that enough voters are myopic enough to forget how bad things have been since 2010.

One of the reasons why the US has performed so much better than the UK since 2019 is that Biden had a clear long term plan of how he was going to support growth, while the UK did not. That plan involved first ensuring a strong vaccine enabled recovery from the pandemic using a fiscal stimulus focused on poorer citizens. Then came large instructure projects, followed last year with incentives for greening the economy. In contrast the strategy of the Conservative government since 2010 has involved shrinking government, tax cuts for firms and Brexit. The aim was to let an ‘unburdened’ private sector do all the work, and it has been a complete failure.

A conventional pre-election fiscal stimulus runs the risk of encouraging the Bank of England to raise interest rates yet further. That suggests he will look at measures that increase aggregate supply as well as aggregate demand, and so might be regarded by the Bank as inflation neutral. Trying to increase aggregate supply is laudable of course, but unfortunately he is likely to shun the two most obvious choices: more public investment and better health.

In his Autumn Statement he had already cut back on public investment, and it will be interesting if he goes further. Delaying the completion of HS2 is an example of what John Elledge had earlier called ‘Treasury brain’. Such delays in investment rarely save money in the longer term, and obviously they delay getting the benefit of the investment. It’s not as if the UK is ‘world beating’ with high speed rail - it’s actually way behind much of Europe. What is important here is not the rhetoric, which is always positive in Budget speeches, but the actual numbers for aggregate public investment, which I will report on in the postscript after the Budget. With so many good reasons to increase public investment in so many areas, it is so short sighted to be cutting it back. If public net investment over the next few years remains below 3% of GDP this will be a consequence of the stupidity of including public investment in the fiscal rule targets.

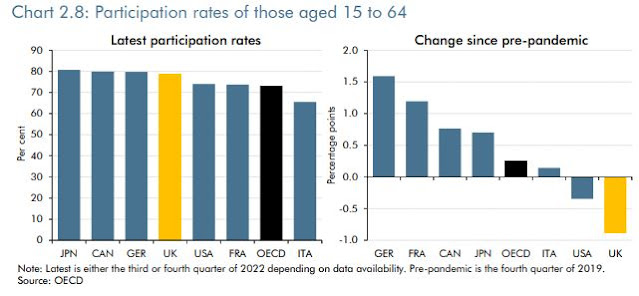

The Chancellor will probably do something to tackle the large number of inactive people of working age that is one of the two key factors behind the UK’s current labour shortage (the other is Brexit). However, as this report argues, the main reason why this problem has been so uniquely persistent in the UK since the pandemic is the large number of people not working because they are sick, which in turn reflects the chronic state of the NHS after thirteen years of Conservative government.. Providing more money to the NHS (the report dubs this “check-ups to pay cheques”) is the best way to achieve this. Yet other reports suggest that the Treasury is trying to stop plans for more NHS nurses and doctors, which in turn suggests the Chancellor is unlikely to provide assistance where it can be most effective.

One area where he may well act to increase demand and supply is incentives for investment by firms. While these incentives generally sound like a good idea, there is a danger that all they do is bring forward investment to years where the incentive applies from years when it doesn’t. If that is all that happens then little has been achieved from a long term point of view, yet with the cost of government payouts to the firms doing the intertemporal switching. However if the Chancellor wants to boost investment in an election year, at the expense of lower investment under what may well be a Labour government, this may not be his major concern!

Low public investment, ignoring the long term sick, and politically motivated subsidies to firms are all examples of where poor political decisions mean that fiscal policy fails to improve the economy in the longer term. If the headline grabbing giveaways include not raising petrol duty yet again, then we can add that to the list. The media will report this as ‘popular with motorists’, as if motorists are united in welcoming climate change.

As I noted in this post, the United States has for the first time a clear plan to encourage the kind of green industries which will play such an important part in all major economies over the next few decades. As their plan is also protectionist, it has encouraged the EU to increase subsidies for these industries. The UK needs its own response. As Torsten Bell points out, it cannot just be an attempt to duplicate what the US and EU are doing, because the UK is a smaller, more open economy that needs to play to its strengths. It will be interesting if we get any idea from the Budget about whether the current government has started to think about what the UK’s strategy on encouraging green industries should be, or whether it is continuing with the failed plan of hoping general corporate tax breaks will invigorate the economy.

Budget Postscript (16/03/23)

There were few surprises in this budget, so the comments above still largely apply. The government's strategic vision, in so far as it exists, remains to squeeze public services and to hope giving money to (a few) individuals and (temporarily) to firms spurs a strong recovery. The response to new green subsidies in the US and EU will have to wait until a little later, but when public investment is not expected to increase beyond this year I wouldn't hold your breath. (OBR Table A.1). The budget also confirmed the expected death of any grand levelling up strategy, although the small amounts allocated are perhaps better directed.

The two welcome measures not covered above were abolishing Work Capability Assessments and the expansion of free child care for very young children. According to the OBR the latter should increase GDP by about 0.2%. Although what was announced will certainly increase the demand for child care, questions remain about whether supply of child care will increase to match this (see also here).

As the OBR notes, the main reason labour supply has shrunk in the UK, by far more than in other economies (see chart below), is the increase in long term sickness. To reverse this requires more money for the NHS, and there was nothing in the budget to help with this.

Tax breaks for firms to increase investment were announced as expected, but only for three years, meaning that the OBR expects them to do little more than shift investment expenditure forward, as suggested above. As the following OBR chart shows, even this is small compared to the collapse in investment caused by Brexit.

Listening to a bit of Hunt's Budget speech, I remembered how I once wrote a few posts pointing out the macroeconomic errors in George Osborne or David Cameron's speeches. I just couldn't do that now, because the posts would be far too long. Almost every sentence is misleading nonsense. I got to sentence number nine before I found something I couldn't take apart: the sentence was “But that’s not all we’ve done.” This may reflect a deterioration in the quality of the Chancellor's speech writers, but I expect it's more that they just have no good material to work with. Can a few tax cuts next year and an economy just starting to grow again really offset in voters minds what has been the most dismal thirteen years for the UK economy since WWII?

No comments:

Post a Comment

Unfortunately because of spam with embedded links (which then flag up warnings about the whole site on some browsers), I have to personally moderate all comments. As a result, your comment may not appear for some time. In addition, I cannot publish comments with links to websites because it takes too much time to check whether these sites are legitimate.