Labour’s current policy on Brexit is designed to help them win power. There is nothing the government and their press would like more than to suggest Starmer intends to undo Brexit, and so the policy of “making [hard] Brexit work” is tailored to remove any credibility from such a claim. However the moment Labour wins power other considerations come into play.

In power Labour becomes responsible for the health of the economy, and Brexit has undoubtedly brought severe damage to the economy and average incomes. Starmer knows this, which is perhaps why he added “at this stage” when saying joining the Single Market would not help growth. In power he will not be able to avoid two clear truths. The first is that, Northern Ireland Protocol apart, the economic effects of being more cooperative with Europe within the context of Johnson’s hard Brexit are small. The second is that the gains from joining the EU’s customs union and, even more so, their single market are certainly not small, just as the costs of leaving both have not been small.

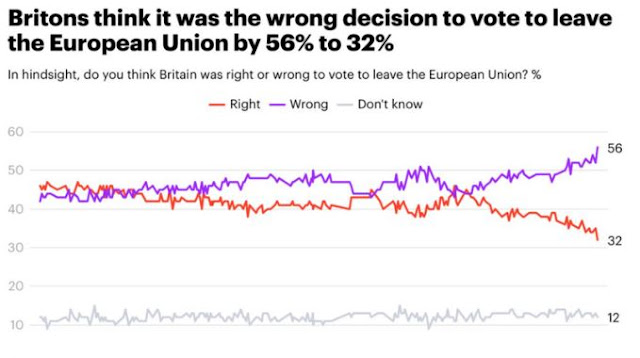

The dangers of alienating those voters who still identify with Brexit will remain, or more generally worrying those voters who fear that changing the Brexit deal in a fundamental way would paralyse the government just as the Brexit referendum did. However the size of the first group will diminish over time, in part because of simple demographics. The size of the second group will also diminish if Labour manages to handle negotiations with the EU over more minor matters with little fuss.

In addition, as Stephen Bush notes, “a Labour government would free up vast swaths of civic society and lobbying organisations, many of which think that Brexit is a disaster but feel they have to pussyfoot around the topic to remain on Downing Street’s Christmas card list”. I noted two weeks ago that we had passed a turning point, where the costs of Brexit had become so evident that the broadcast media felt compelled to start talking about them. With the focus on a Labour rather than Conservative government, there will be fewer voices defending Johnson’s Brexit deal and many more pointing out its problems.

Indeed, it seems likely that one of the last groups to change their mind on Brexit will be the Conservative party. This, combined with this trend in public opinion away from either believing in Brexit or fearing its modification, means that at some point support for Johnson’s Brexit deal (or something even harder) will become an electoral liability for the Conservatives. As it becomes clearer that Brexit has reduced living standards and held the economy back, an attachment to the policy will be associated with a party that wants to keep the country poorer.

There is therefore a tipping point in public opinion, when suggesting Johnson’s hard Brexit deal needs to be thrown in the dustbin of history no longer becomes a political liability but a political necessity for Labour. Some may think we have already reached that tipping point, but two key factors suggest otherwise. The first is that FPTP helps Brexit supporters, and works against those who want to change Brexit, because the latter are concentrated in cities. The second is that Brexit regret does not necessarily imply a wish to change Johnson’s Brexit deal, because the prospect of reopening the Brexit question reminds many of the three years after the referendum.

It may seem hard to imagine passing this tipping point, because before we get to that tipping point the opposite is true, hence Labour’s current commitment to making Brexit work. But the big Brexit divide cuts both ways, so that when enough voters see Brexit as a mistake that needs a fundamental correction it will become politically advantageous to argue for that correction, and a political liability to oppose this. Then the costs for the Conservatives of championing a policy mainly favoured by the elderly that incurs serious economic costs will finally come home to roost.

Labour are unlikely to reverse their current Brexit policy immediately on taking office. They should instead immediately start discussions with the EU about “making Brexit work”. It is important that such discussions start quietly and without diverting attention from more immediate concerns. It would for the same reason be an obvious political mistake to raise expectations about what such negotiations can achieve, because any economic gains that follow will be small. But the existence of a tipping point for public opinion on Brexit means not only that Labour need to be prepared to switch from making Brexit work to changing Brexit during their time in government, but also that it is in Labour’s interests to do anything it can to hasten the arrival of that tipping point.

The Conservatives ability to tag Miliband’s Labour party with economic incompetence was crucial in winning the 2015 election, and Johnson’s Brexit deal can do the same for a Labour party once it holds power. It is therefore in a Labour government’s interests, assuming we have one in 2025, to be as open and honest as possible about both the economic advantages of the alternative ways of softening a hard Brexit, and also about what is and is not possible in terms of any deals with the EU.

That raises the question as to when Labour should begin to suggest the possibility of going further, which in practice will almost certainly mean rejoining the EU’s customs union and/or single market? Should this happen during Labour’s first term, or its intended second term?

The point at which Labour changes from doing what it can with a hard Brexit to changing Brexit will depend on many things beside the tipping point in public opinion, such as the pressure from domestic events and willingness on the EU side of the table. Two other factors are worth noting here. The first is the likely lag between any agreement (which itself will take time) and the economic benefits that would follow. If one of key reasons for a Labour government to change Brexit would be to benefit the economy and therefore household incomes and public services, the sooner this happens the better.

This suggests moving as quickly as is feasible to join the EU’s customs union. While the economic benefits are probably less than being part of the single market, it would remove some of the paperwork that small businesses in particular find is a barrier to exporting to the EU. It would also provide a good excuse to revise or end the few genuinely new trade deals obtained by Liz Truss, which seem lopsided to the detriment of some UK sectors. There may also be some gains to be made through alignment of standards, cooperation in research etc.

In assessing the likelihood of the UK joining the single market we need to consider a second factor influencing timing, and that is the behaviour of the Conservative party in opposition. If the Labour government benefits from the economic recovery that follows from the current recession, then - as with the last Labour government - the Conservatives will have to focus on social rather than economic issues. Just as with the last Labour government, immigration is likely to be their most effective issue.

Attitudes to immigration have been changing over the last decade, but it remains the most potent social issue among potential Conservative voters. Furthermore, how important those voters feel that immigration is compared to other issues depends a great deal on how much coverage it is given in the Conservative press. That in turn will depend on whether the Conservatives are in power or not. [1] Newspaper stories about immigration or asylum seekers are therefore likely to begin to increase under a Labour government, and public concern will rise along with it.

It is therefore immigration, rather than attitudes to Brexit per se, that is likely to be the main barrier to Labour trying to negotiate membership of the Single Market, because of course that membership requires free movement of labour within that market. The best way Labour have to moderate this Conservative weapon is to move to some form of PR for general elections, for reasons noted above. There may be other means of making free movement politically acceptable, as Peter Kellner suggests here.

None of these arguments guarantees that Labour will or will not try to negotiate to join the Single Market, but they do suggest that negotiations to join the Single Market will be one of the last stages in the long road back from Brexit.

However this should not stop Labour being honest about the economic costs of leaving the EU’s single market, and therefore the benefits of joining. Chris Grey suggests an interesting additional idea, which is that Labour suggests that it would be unwise (or the EU might be unwilling) to consider the UK being part of the Single Market until there is cross-party agreement that this should happen. This would have the political benefit, for Labour, of emphasising the economic costs of the Conservative’s continuing attachment to a hard Brexit.

To summarise, the existence and proximity of a tipping point on public opinion about Brexit means it is important for any Labour government from 2025 to be open and honest about Brexit’s economic costs and what can and cannot be achieved in negotiations. It also means that it is quite possible to see Labour moving beyond ‘making Brexit work’ once they have power, although rejoining the Single Market remains the most difficult move in political terms.

Once the tipping point is passed, believing in a hard Brexit will become a serious political disadvantage for the Conservatives. Yet what is difficult to imagine is how they will escape from what will become a serious drag on their popularity. Johnson and others have made Brexit part of the Conservative party’s DNA. The conditions that make me confident in saying that no Conservative government will change a hard Brexit for at least a decade also make it difficult imagining them renouncing the policy in opposition. Perhaps it will take many years in opposition for MPs, but also crucially party members and the owners of the right wing press, to realise what a liability Brexit support is for them.

[1] The exception was during the Cameron government, but I don’t think it would be overly cynical to say that this had a great deal to do with Brexit, which the press favoured and Cameron did not. The data supports this, with the number of articles mentioning immigration rising rapidly from 2013 until 2016.

The best recent article I have seen on Brexit (including Chris Grey).

ReplyDeleteRegarding the latter point (alluded by Grey) that a cross party SM consensus may be required to satisfy the EU of our reliability - I have seen no evidence from any EU source for this argument. In reality, there would already be an overwhelming consensus - Labour/LD/SNP/Green - plus of course many erstwhile or purged Conservatives. What is more, any future Brexit 2 would face an almost impossible democratic hurdle, given demographics and the scarring of the current Brexit reality.

What would make the Conservative Party change it's hard Brexit ideology in less than a decade is a major defeat at the next election with those who most strongly supported the rather naive promises of the benefits of Brexit (for example the farmers and many red wall voters) complaining loudly that they have actually suffered because of the decision to leave.

ReplyDeleteThe problem with your analysis is that you assume the UK *can* rejoin the EU or the Single Market. You cannot. The remaining EU countries have absolutely zero interest in allowing you back in, knowing that the Conservatives will just kick off Brexit II the next time they're in power (which they would). "Making Brexit work" is literally the only option left. You've made your bed, now you have to lie in it.

ReplyDeleteAgree with your argument but I think Labour should now be taking the position of rejoining the customs union to remove much of the paperwork and make trade with the EU easier without free movement. It would be likely the EU would buy into this to make life easier to export to the UK.

ReplyDeleteFine, but all this assumes the EU will have us back or agree terms for soft Brexit. Far from evident.

ReplyDeleteThank your for your post. Please note though that the following text, from the post, is garbled: 'But strikes are not an isolated example in an otherwise sea of policies'. Further, 'they want less asylum seekers' should be: 'they want fewer [. .]'.

ReplyDelete