An interesting

disagreement

occurred this week between Martin Sandbu and the Economist, which

prompted a subsequent letter

from Philippe Legrain (see also Martin again here).

The key issue is whether the German current account surplus, which

has steadily risen from a small deficit in 2000 to a large surplus of

over 8% of GDP, is a problem or more particularly a drag on global

growth.

To assess whether

the surplus is a problem, it is helpful to discuss a key reason why

it arose. I have talked about this in detail many times before, and a

similar story has been told

by one of the five members of Germany’s Council of Economic

Experts, Peter Bofinger.

A short summary is that from the moment the

Eurozone was born Germany allowed wages to increase at a level that

was inconsistent with the EZ inflation target of ‘just below 2%’.

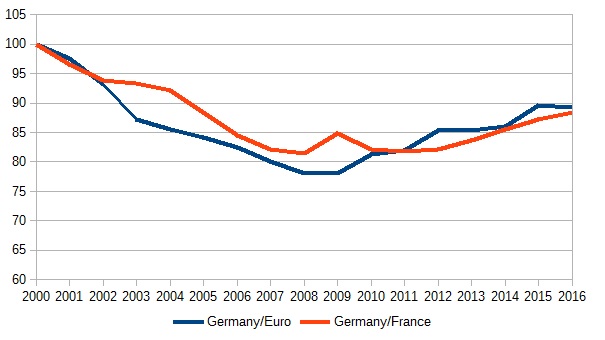

We can see this clearly in the following chart.

Relative unit labour

costs, source OECD Economic Outlook, 2000=100

The blue line shows

German unit labour costs relative to its competitors compared to the

same for the Euro area average. Obviously Germany is part of that

average, so this line reduces the extent of any competitiveness divergence between

Germany and other union partners. By keeping wage inflation low from

2000 to 2009, Germany steadily gained a competitive advantage over

other Eurozone countries.

At the time most

people focused on the excessive inflation in the periphery. But as

the red line shows, this was only half the story, because wage

inflation was too low in Germany compared to everyone else. This

growing competitive advantage was bound to lead to growing current

account surpluses.

However that in

itself is not enough to say there is a problem, for two related

reasons. First, perhaps Germany entered the Eurozone at an

uncompetitive exchange rate, so the chart above just shows a

correction to that. Second, perhaps Germany needs to be this

competitive because the private sector wants to save more than it

invests and therefore to buy foreign assets.

There are good

reasons, mainly to do with an ageing population, why the second point

might be true. (If it was also true in 2000, the first point could

also be true.) It makes sense on demographic grounds for Germany to

run a current account surplus. The key issue is how big a surplus.

Over 8% of GDP is huge, and I have always thought that it was much

too big to simply represent the underlying preferences of German

savers.

I’m glad to see

the IMF agrees. It suggests

that a current account surplus of between 2.5% to 5.5% represents a

medium term equilibrium. That would suggest that the competitiveness

correction that started in 2009 has still got some way to go. Why is

it taking so long? This confuses some into believing that the 8%

surplus must represent some kind of medium term equilibrium, because

surely disequilibrium caused by price and wage rigidities should have

unwound by now. The answer to that can also be found in an argument

that I and others put forward

a few years ago.

For this

competitiveness imbalance to unwind, we need either high wage growth

in Germany, low wage growth in the rest of the Eurozone, or both.

Given how low inflation is on average in the Eurozone, getting below

average wage inflation outside Germany is very difficult. The

reluctance of firms to impose wage cuts, or workers to accept them, is well known. As a result, the unwinding of competitiveness

imbalances in the Eurozone was always going to be slow if the

Eurozone was still recovering from its fiscal and monetary policy induced recession and therefore Eurozone average inflation was low. [1]

In that sense German

current account surpluses on their current scale are a symptom of two

underlying problems: a successful attempt by Germany to undercut

other Eurozone members before the GFC, and current low inflation in

the Eurozone. To the extent that Germany can make up for their past

mistakes by encouraging higher German wages (either directly, or

indirectly through an expansionary fiscal policy) they should. Not

only would that speed adjustment, but it would also discourage a

culture within Germany that says it is generally legitimate to

undercut other Eurozone members through low wage increases. [2]

From this

perspective, does that mean that the current excess surpluses in

Germany are a drag on global growth? Only in a very indirect way. If

higher German wages, or the means used to achieve them, boosted

demand and output in Germany then this would help global growth.

(Remember that ECB interest rates are stuck at their lower bound, so

there will be little monetary offset to any demand boost.) The

important point is that this demand boost is not so that Germany can

help out the world or other union members, but because Germany should

do what it can to correct a problem of its own making.

[1] Resistance to

nominal wage cuts becomes a much more powerful argument for a higher

inflation target in a monetary union where asymmetries mean

equilibrium exchange rates are likely to change over time.

[2] The rule in a

currency union is very simple. Once we have achieved a

competitiveness equilibrium, nominal wages should rise by 2% (the

inflation target) more than underlying national productivity. I

frequently get comments along the lines that setting wages lower than

this improves the competitiveness of the Eurozone as a whole. This is

incorrect, because if all union members moderate their wages in a

similar fashion EZ inflation would fall, prompting a monetary

stimulus to bring inflation back to 2% and wage inflation back to 2%

plus productivity growth.