My discussion about current inflation two weeks ago focused on the UK. Over a year ago I wrote a post called “Inflation and a potential recession in 4 major economies”, looking at the US, UK, France and Germany. I thought it was time to update that post for countries other than the UK, with the UK included for comparison and with Italy added for reasons that will become clear. I also want to discuss in general terms how central banks should deal with the problem of knowing when to stop raising interest rates, now that the Fed has paused its increases, at least for now.

How to set interest rates to control inflation

This section will be familiar to many and can be skipped.

If there were no lags between raising interest rates and their impact on inflation then inflation control would be just like driving a car, with two important exceptions. Changing interest rates is like changing the position of your foot on the accelerator (gas pedal), except that if the car’s speed is inflation then easing your foot off the pedal is like raising rates. So far so easy.

Exception number one is that, unlike nearly all drivers who have plenty of experience driving their car, the central banker is more like a novice who has only driven a car once or twice before. With inflation control, the lessons from the past are few and far between and are always approximate, and you cannot be sure the present is the same as the past. Exception number two is that the speedometer is faulty, and erratically wobbles around the correct speed. Inflation is always being hit by temporary factors, so it’s very difficult to know what the underlying trend is.

If driving was like this, the novice driver with a dodgy speedometer should drive very cautiously, and that is what central bankers do. Rapid and large increases in interest rates in response to increases in inflation might slow the economy uncomfortably quickly, and may turn out to be an inappropriate reaction to an erratic blip in inflation. So interest rate setters prefer to take things slowly by raising interest rates gradually. In this world with no lags our cautious central banker would steadily raise interest rates until inflation stopped increasing for a few quarters. Inflation would still be too high, so they might raise interest rates once or twice again to get inflation falling, and as it neared its target cut rates to get back to the interest rate that kept inflation steady. [1]

Lags make the whole exercise far more difficult. Imagine driving a car, where it took several minutes before moving your foot on the accelerator had a noticeable impact on the car’s speed. Furthermore when you did notice an impact, you had little idea whether that was the full impact or there was more to come from what you did several minutes ago. This is the problem faced by those who set interest rates. Not so easy.

With lags, together with little experience and erratic movements in inflation, just looking at inflation would be foolish. As interest rates largely influence inflation by influencing demand, an interest rate setter would want to look at what was happening to demand (for goods and labour). In addition, they would search for evidence that allowed them to distinguish between underlying and erratic movements in inflation, by looking at things like wage growth, commodity prices, mark-ups etc.

Understanding current inflation

There are essentially two stories you can tell about recent and current inflation in these countries, as Martin Sandbu notes. Both stories start with the commodity price inflation induced by both the pandemic recovery and, for Europe in particular, the war in Ukraine. In addition the recovery from the pandemic led to various supply shortages.

The first story notes that it was always wishful thinking that this initial burst of inflation would have no second round consequences. Most obviously, high energy prices would raise costs for most firms, and it would take time for this to feed through to prices. In addition nominal wages were bound to rise to some extent in an attempt to reduce the implied fall in real wages, and many firms were bound to take the opportunity presented by high inflation to raise their profit margins (copy cat inflation). But just as the commodity price inflation was temporary, so will be these second round effects. When headline inflation falls as commodity prices stabilise or fall, so will wage inflation and copy cat inflation. In this story, interest rate setters need to be patient.

The second story is rather different. For various (still uncertain) reasons, the pandemic recovery has created excess demand in the labour market, and perhaps also in the goods market. It is this, rather than or as well as higher energy and food prices, that is causing wage inflation and perhaps also higher profit margins. In this story underlying inflation will not come down as commodity prices stabilise or fall, but may go on increasing. Here interest rate setters need to keep raising rates until they are sure they have done enough to eliminate excess demand, and perhaps also to create a degree of excess supply to get inflation back down to target.

Of course reality could involve a combination of both stories. In last year’s post I put this collection of countries into two groups. The US and UK seemed to fit both the first and second story. The labour market was tight in the US because of a strong pandemic recovery helped by fiscal expansion, and in the UK because of a contraction in labour supply partly due to Brexit. In France and Germany the first story alone seemed more likely, because the pandemic recovery seemed fairly weak in terms of output (see below).

Evidence

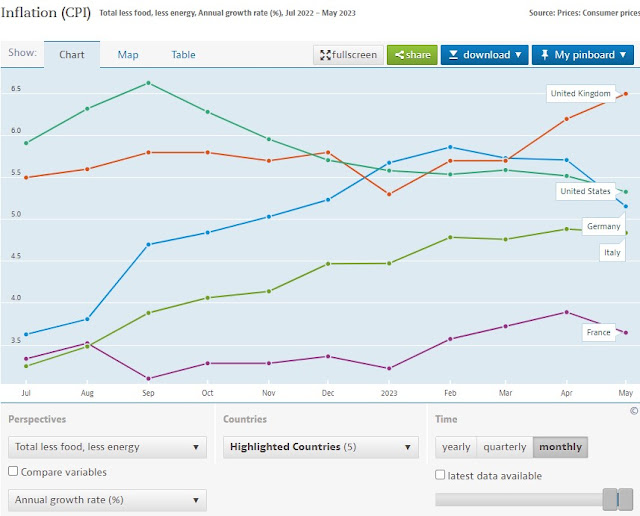

In my post two weeks ago I included a chart of actual inflation in these five countries. Here is a measure of core inflation from the OECD that excludes all energy and food, but does not exclude the impact of (say) higher energy prices on other parts of the index because energy is an important cost.

Core inflation is clearly falling in the US (green), and rising in the UK (red). In Germany (light blue) core inflation having risen seems to have stabilised, and the same may be true in France and Italy very recently. The same measure for the EU as a whole (not shown) also seems to have stabilised.

If there were no lags (see above) this might suggest that in the US there is no need to raise interest rates further (as inflation is falling), in the UK interest rates do need to rise (as they did last month), while in the Eurozone there might be a case for modest further tightening. However, once you allow for lags, then the impact of the increases in rates already seen has yet to come through, so the case for keeping US rates stable is stronger, the case for raising UK rates less clear (the latest MPC vote was split, with 2 out of 7 wanting to keep rates unchanged) , and the case for raising rates in the EZ significantly weaker. (The case against raising US rates increases further because of the contribution of housing, and falling wage inflation.)

As we noted at the start, because of lags and temporary shocks to inflation it is important to look at other evidence. A standard measure of excess demand for the goods market is the output gap. According to the IMF, their estimate for the output gap in 2023 is about 1% for the US (positive implies excess demand, negative insufficient demand), zero for Italy, -0.5% for the UK (and the EU area as a whole), and -1% for Germany and France. In practice this output gap measure just tells you what has been happening to output relative to some measure of trend. Output compared to pre-pandemic levels is strong in the US, has been pretty strong in Italy, has been quite weak in France, even weaker in Germany and terrible in the UK (see below for more on this).

I must admit that a year ago this convinced me that interest rate increases were not required in the Eurozone. However if we look at the labour market today things are rather different. Ignoring the pandemic period, unemployment has been falling steadily since 2015 in both Italy and France, and for the Euro area as a whole it is lower than at any time since 2000. In Germany, the US and UK unemployment seems to have stabilised at historically low levels. This doesn’t suggest insufficient demand in the labour market in the EZ. Unemployment data is far from an ideal measure of excess demand in the labour market, so the chart below plots another: employment divided by population, taken from the latest IMF WEO (with 23/24 as forecasts).

Once again there is no suggestion of insufficient demand in any of these five countries. (The UK is the one exception, until you note how much the NHS crisis and Brexit have reduced the numbers available for work since the pandemic.)

This and other labour market data suggests our second inflation story outlined in the previous section may not just be true for the US and UK, but may apply more generally. It is why there is so much focus on wage inflation in trying to understand where inflation may be heading. Of course a tight labour market does not necessarily imply interest rates need to rise further. For example in the US both wage and price inflation seem to be falling despite a reasonably strong labour market, as our first inflation story suggested they might. The Eurozone is six months to a year behind the US in the behaviour of both price and wage inflation, but of course interest rates in the EZ have not risen by as much as they have in the US.

Good, bad and ugly pandemic recoveries

The chart below looks at GDP per capita in these five countries, using the latest IMF WEO for estimates for 2023.

Initially I will focus on the recovery since the pandemic, so I have normalised all series to 100 in that year. The US has had a good recovery, with GDP per capita in 2023 expected to be five percent above pre-pandemic levels. So too has Italy, which is forecast to do almost as well. This is particularly good news given that pre-pandemic levels of GDP per capita were below levels achieved 12 years earlier in Italy.

Germany and France have had poor recoveries, with GDP per capita in 2023 expected to be similar to 2019 levels. The UK is the ugly one of this group, with GDP per capita still well below pre-pandemic levels, something I noted in my post two weeks ago. Unlike a year ago, there is no reason to think these differences are largely caused by excess demand or supply, so it is the right time to raise the question of why there has been such a sharp difference in the extent of bounce back from Covid. To put the same point another way, why has technical progress apparently stopped in Germany, France and the UK since 2019.

Part of the answer may be that this reflects long standing differences between the US and Europe. Here is a table illustrating this.

|

Real GDP per capita growth, average annual rates |

2000/1980 |

2007/2000 |

2019/2007 |

2023/2019 |

|

France |

1.8 |

1.2 |

0.5 |

0.1 |

|

Germany |

1.8 |

1.4 |

1.0 |

-0.1 |

|

Italy |

1.9 |

0.7 |

-0.5 |

0.8 |

|

United Kingdom |

2.2 |

1.8 |

0.6 |

-0.7 |

|

United States |

2.3 |

1.5 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

Growth in GDP per capita in the US has been significantly above that in Germany, France or Italy since 1980. At least part of that is because Europeans have chosen to take more of the proceeds of growth in leisure. However this difference is nothing like the gap in growth that has opened up since 2019. (I make no apology in repeating that growth in the UK, unlike France or Germany, kept pace with the US until 2007, but something must have happened after that date to reverse that.)

I have no idea why growth in the US since 2019 has been so much stronger than France or Germany, but only a list of questions. Is the absence of a European type furlough scheme in the US significant? Italy suggests otherwise, but Italy may simply have been recovering from a terrible previous decade. Does the large increase in self-employment that occurred during the pandemic in the US have any relevance? [1] Or are these differences nothing to do with Covid, and instead do they just reflect the larger impact in Europe of higher energy prices and potential shortages due to the Ukraine war. If so, will falling energy prices reverse these differences?

[1] If wage and price setting was based on rational expectations the dynamics would be rather different.

[2] Before anti-lockdown nutters get too excited, the IMF expect GDP per capita in Sweden to be similar in 2023 to 2019.