Noah Smith has a

good piece

on what seems like the never ending stream of popular articles in the

UK slagging off economics (or economists). Here

I outlined three potential reasons for this epidemic: people do not

understand unconditional macro forecasts, politicians from the right

do not like economists spoiling their pet schemes (e.g. Brexit), and

many heterodox economists from the left wage endless war against the

mainstream. All these complaints get airtime when the economy is bad.

The UK economy,

right now, is perhaps in a worse state than at any time in the last

eighty years. As John Lewis shows in this Bank blog, productivity

growth has perhaps never been as bad as it is now: we have to go back

to before 1800 to find anything comparable.

The natural reaction when the economy is bad is to criticise economists. That was what happened after the Global Financial Crisis, with some justification. But what is happening in the UK right now is mainly a result of first austerity and then Brexit. As I explained in detail in my earlier post, if we had followed the advice of mainstream economics austerity and Brexit would not have happened. [1] I have as yet not read a single critique of economics that has pointed that fact out, which if you think about it is extraordinary.

There is a little

more to say about why economics is an easy target. Historically it

has been very insular, and in this respect quite unlike other social

sciences. I have already discussed the paper

by Haldane and Turrell in the OXREP Rebuilding Macroeconomic Theory

volume on Agent Based Models, but I did not have space to show an

interesting chart from the introduction to that paper.

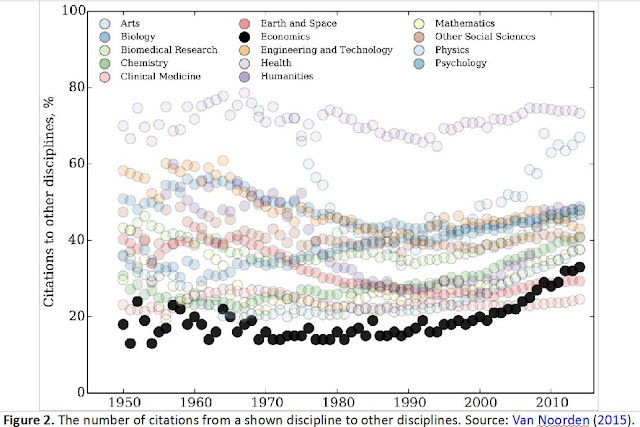

It tracks citations

in papers to those in other disciplines. Until around 2000, there

was no doubt which was the most insular discipline: economics. This

is no surprise to me and I suspect most social scientists.

The paper does not

explore the reasons why economics is so self-referential: their aim

is simply to suggest that it needs to look to other disciplines to

see what methods they use. Here I want to sketch why I think

mainstream economics (and here the qualification mainstream is

required) is so insular.

I once gave a

lecture course on the methodology of economics, and in one lecture I

used a large blackboard to describe how nearly all economics can be

derived from the basic axioms of rational choice. For example the

modern macroeconomics of consumption is just the choice between

buying apples or pears transformed to the choice between consumption

at different times. In that sense economic theory is like an immense

tree, where every branch deductively builds on this core. Sometimes

large branches grow by adding new elements, like asymmetric

information, which then becomes part of the tree and can be used by

other branches. This deductive tree of economic theory did not grow

all by itself: its growth was and is influenced by the real world

problems it wanted to address.

In using the idea of explaining decisions by optimising welfare under constraints economists have created a whole

series of widely applicable tools. Economists naturally think about

opportunity costs, adverse selection, moral hazard, incentives etc. There is something distinctive about thinking like an economist. To say, as Tom Clark does here,

that sometimes this is just formalising common knowledge may be true

(see also Cahal Moran here),

but in many cases it is not. Try persuading someone who has invested

in what is now a sub-optimal project about sunk costs.

This body of theory

includes the neoclassical economics that heterodox economists and

others love to hate, but it also includes game theory that has

applications well beyond economics, and more. In my first year of studying

economics I was told in some lectures that this whole endeavour was a huge

ideologically driven misstep, but I began to see it differently after

reading this famous 1963 paper

by Arrow. It shows why (asymmetric) uncertainty in the health service

means that the standard competitive model just cannot work for

medical care. That may be obvious to us in the UK but it appears otherwise to many in the US. To be fair Clark also acknowledges that this economic theory has

produced positive successes: he mentions auction theory but there are

many

more.

As to ideology, if

you want an effective critique of neoliberalism you have to use

economics (see, for example Colin Crouch’s book

on neoliberalism or this

by Dani Rodrik). So many critiques of economics use a kind of

bastardised version that insists that workers are always paid their

marginal products that the political right also employs. But monopoly

and monopsony power are also part of the deductive tree. A paper I

like to refer to in this context is by Piketty, Saez and Stantcheva (discussed here) which uses a simple bargaining model to show how cutting the top rate

of tax can increase pre-tax CEO pay.

There is nothing

like this deductive tree in other social sciences, and I think it at

least partly explains why economics used to be so insular. As

non-economists academics seemed to add little to building on this

theory, there seemed little point in collaborating or even citing

them. But, from the point of view of other disciplines, it was worse

than that. Economics could also be imperialistic. Its methods, both

theoretical and empirical, could be applied to other fields (with

varying degrees of success): here

is David Hendry applying his econometric methods to climate change,

for example. So not only did economists not talk much to other social

sciences, they trod on toes as well.

But although there

may still be important branches to be added [2], the limitations of what

you can do with a few axioms about rational choice have led in recent

years to economics becoming much more empirical, and much less tied

to this deductive theory. (See the article

by Noah Smith which began this post. Unfortunately in my view an

exception to this trend so far is macroeconomics.). We can see this

in the citations data above, and the most obvious manifestation is

behavioural economics. But a more immediate example of a data rather than theory based idea is the gravity

model in international trade, which lies at the heart of why Brexit is such a bad idea. It

is irony indeed that just at the point at which we have all these

articles attacking economics, a large number of people who believe the UK is committing a large act of self harm are seeing the

virtue of just one small part of what economists do.

Having said all

this, I think there is an unfortunate hangover from this insularity.

As a discipline economics shows little interest in

communicating its core knowledge to others [3]. This can be true both

within academia and with the outside world. Within academia

publishing in top economics journals still has far higher status than

top journals in other disciplines. When it comes to policy and the

public, there is a belief among many that when either requires our

wisdom, they will seek out the best of us for advice. In part this

epidemic of articles about the failings of economics reflects this

communication failure. More importantly, both Brexit and Trump should

be a wake up call that economists as a collective has to get better

at communicating the core insights of economics.

[1] There are of

course more underlying problems

behind the UK productivity crisis beyond the negative shocks of

austerity and Brexit. But economists overwhelmingly argue for more

R&D spending and more public investment. In short if you want

someone to blame for why the UK economy is currently in such a dire

state, blame those who have ignored the advice of economists.

[2] Most of the good criticisms that I see of economics amount to requests to add to the tree. But economics is so rich that most things are possible. In part (but only in part) what is done follows the money: you will find it relatively easy to get money for work on free trade compared to work on rent seeking. To blame economists for that is just bad economics. As economists found out after the financial crisis, they had many tools to understand what had happened, but had just not applied them before the crisis.

[3] I say as a discipline because I mean economists as a collective, not as individuals. There is no equivalent institutional infrastructure in economics to that built by the hard sciences. Of course many individual economists do their best, but there are also others who ignore the consensus to plug their own personal ideas or to further some political or ideological cause.